Astronomers say galactic collisions do not cause bigger black holes

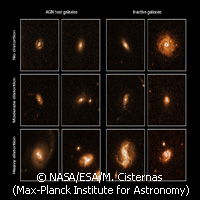

If you thought that galactic collisions are responsible for triggering bigger black holes, think again. New groundbreaking research shows that other, less dramatic phenomena are, in fact, to blame for intensifying galactic black holes. The astronomers will present the findings of their study in the upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal. Experts say the majority of galaxies, including our very own Milky Way, contain massive black holes that are 'obedient' and docile. Other galaxies consume 'vast amounts of matter which then shines brightly as it falls towards oblivion', according to the team. This consumption makes the centre of these galaxies super luminous, what experts call 'active galactic nuclei' (AGN). The big question, however, was 'Why the difference in the two types?' Researchers long speculated that galactic collisions were responsible for stimulating black hole growth by injecting matter into them. This latest study shows this is not the case. The astronomers from France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Switzerland and the US established an identity parade of galaxies to put their theory to the test. They modelled and removed the bright spot that reveals the AGN. They compared 140 active galaxies with a control group of more than 1,200 comparable inactive galaxies. They found no strong connection between AGN activity and galactic mergers for at least the last 8 billion years. In a nutshell, other phenomena like molecular cloud collisions or galactic instabilities are responsible for black hole growth in at least 75% of, cases, if not all of them. The behaviour of matter, including stars and gas clouds, as it heats up and falls into the galaxy's supermassive central black hole is what drives the emission of radiation from active galactic nuclei, the team says. So how does matter cross the final light-years to reach the centre of the black hole before it gets eaten? PhD student Mauricio Cisternas from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, and the leader of the study, says: 'A study of this scope has become possible only recently, as the large surveys undertaken using the Hubble Space Telescope have become available. These have given us a huge sample of galaxies, both active and inactive, meaning that we can now study many distant galaxies in exquisite detail. Before these surveys, we hadn't examined many active galaxies at large cosmic distances in sufficient detail.' Using X-ray observations from the European Space Agency's (ESA) XMM-Newton space telescope, the astronomers identified active galaxies and later assessed them in more detail with optical images generated by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. 'You can usually tell when galaxies have been involved in a merger,' explains Dr Knud Jahnke from Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy. 'Instead of the neat, geometric spiral or smooth elliptical shapes you usually see in Hubble images, colliding galaxies typically look distorted and warped. We planned to find out whether these misshapen galaxies were more likely than regular ones to host active nuclei.' The next puzzle the researchers plan to piece together is to determine whether a causal link between mergers and activity in the more distant past exists. They say they will use data from two ongoing observational programs involving the Hubble Space Telescope, and from observations by its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, which will launch after 2014.For more information, please visit: Hubble European Space Agency Information Centre:http://www.spacetelescope.org/about_us/heic/Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy:http://www.mpia.de/The Astrophysical Journal:http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X/

Countries

Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, United States