Could a cluster of biosensors effectively monitor a wide range of ocean pollution?

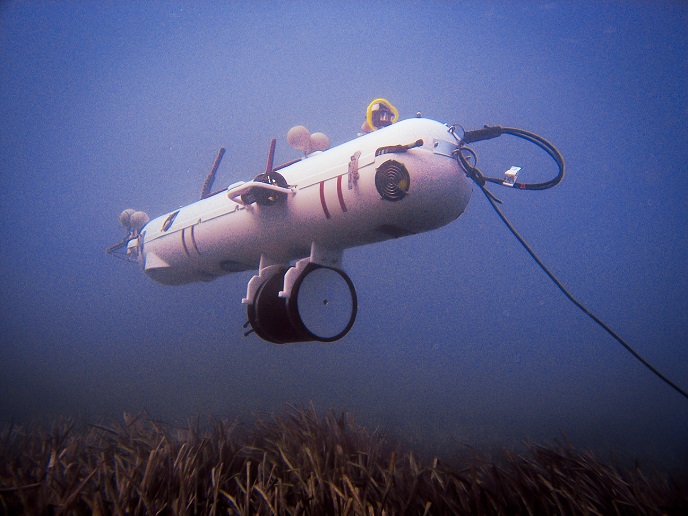

The oceans were once thought big enough to absorb oil spills, toxic waste, floating plastic and more, but it’s now clear that pollution in the oceans is an accelerating problem. ‘In developing sensors to detect polluting toxins in the marine environment, the problem now is deciding which of the thousands of compounds that end up in the seas to monitor,’ says microbiologist, Professor Jan van der Meer, from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland and BRAAVOO project coordinator. ‘Our project decided to target a number of recurrent pollutants for which no easy analysis was available.’ BRAAVOO has developed a unique device using biological sensors, deploying multiple technologies that make it possible to simultaneously identify antibiotics, toxins from algal blooms, endocrine-disrupting chemicals from paints, oil-derived compounds, and toxic heavy metals. The consortium of eight academic and SME partners completed its three-year project in 2016. Each partner designed an element of the monitoring device which formed the complete automated sensor system. Three types of sensors were incorporated into the device - immunosensors that use antibodies to detect specific biological molecules, bacterial biosensors, and a system to detect toxins using the light-dependent reactions occurring in algae. In particular, BRAAVOO combines highly specific biosensors and more general wide spectrum detectors. ‘We wanted to have some biosensors which are very compound-specific, for example, targeting a single antibiotic, or a single algal toxin. However, by deploying very specific biosensors, one might miss other toxins in the water, therefore, we also included very general biosensors that react to anything that may be toxic,’ explains van der Meer. Detecting toxicity isn't always easy because it isn’t always know what to look for, but BRAAVOO took the approach of detecting the biological effects of toxicity on cells rather than only detecting chemical substances of known toxicity. For example, van der Meer says, ‘Looking at evidence of bacterial stress provides a very sensitive detector of toxic compounds or combinations of compounds in the water that will cause toxicity to other living things.’ Three ingenious biological sensing methods have been utilised in BRAAVOO’s device which was designed to be integrated in a marine buoy for automated analysis. Immunosensors deploy an antibody that will bind to target compounds. ‘The innovation here was detecting very small changes in the size of the interacting antibody-target complex which enables miniaturisation of the assay,’ says van der Meer. Bacterial sensors used freeze-dried cells that, when in contact with a chemical target, such as mercury or cadmium, cause bioluminescence. The amount of light produced is a measure for the level of chemical exposure. The third sensor used immobilised marine algae in small beads which are exposed to a sample in an incubation chamber where flourescence can be detected. Testing the system in real life was challenging, because, says van der Meer, ‘We couldn’t first control the level of contamination present in the sea.’ So they used a mesocosm - a tank big enough to contain the system which was artificially contaminated. The device was also successfully tested off the coast of Ireland. Whilst a prototype for commercialisation was not pursued due to limited resources, the algal detection system is now being developed by Biosensor SRL in Italy.