Herschel delivers 'spectacular' results

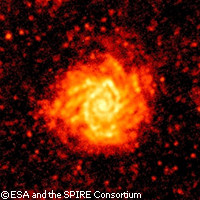

Early trials of the instruments on board the European Herschel satellite have produced spectacular images of the Universe. The results of these test observations were far better than anyone had expected and astronomers are now extremely optimistic about the scientific studies lined up for Herschel over the coming months and years. Professor Robert Kennicutt of Cambridge University in the UK, who plans to use Herschel to study nearby galaxies, said he was 'thrilled' at the pictures of two of the galaxies he is studying. 'They reveal the cold dust and star formation in these galaxies in stunning detail, and are a sneak preview of future observations that promise to revolutionise our understanding of star formation in the Universe,' he commented. Herschel was launched into space on 14 May this year. The 3.4-tonne Herschel observatory boasts the largest telescope to be flown in space and bears three instruments: SPIRE (Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver), PACS (Photodetector Array Camera and Spectrometer) and HIFI (Heterodyne instrument for the Far-Infrared). Herschel and its instruments are designed to help astronomers study star and galaxy formation; investigate the composition of comets and planetary atmospheres in the Solar System; and examine the dust ejected by dying stars - a process that provides the raw materials for planets like Earth. The instruments were switched on for the first time in the first couple of weeks after the launch of the satellite. Since then, researchers have been fine-tuning them and will continue to do so until the end of July. On 24 June, SPIRE was pointed at two galaxies: M74, a spiral galaxy lying 24 million light years from Earth in the constellation Pisces; and M66, a barred spiral galaxy located around 36 million light years away in the constellation Leo. The images captured by SPIRE give astronomers the best images yet of these galaxies at these wavelengths. As well as displaying the galaxies' spiral arms in great detail, the SPIRE images reveal the cold dust found between the stars in the galaxies. Furthermore, the images have many faint dots: distant galaxies in the background. 'We have dreamed of seeing such images for a very long time, more than 10 years. And they are an achievement: the first real images in the far infrared, opening a new window in astronomy,' said Laurent Vigroux of CEA/IRFU Saclay and Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, France. 'These images are the start of another 10 years or more of work to exploit all the scientific results that SPIRE will produce.' Herschel's other instruments are also performing well. PACS' first test saw it investigate the Cat's Eye Nebula, a dying star that was discovered by William Herschel in 1786. The PACS pictures reveal for the first time how the wind from the star shapes the nebula in three dimensions. The HIFI instrument also provided valuable data on its first outing, revealing the elements present in a region where new stars are formed. 'These quick, first-light observations have produced dramatic results when we consider that they were made on day one,' noted co-SPIRE Principal Investigator Professor Matt Griffin of Cardiff University in the UK. 'Astronomers planning to use SPIRE are delighted because they can see straight away that the main scientific studies planned with the instrument are going to work extremely well,' Professor Griffin pointed out. 'In fact all three instruments on Herschel have now shown what they can do, and the results are spectacular all round.' The Herschel satellite is now approaching its final operation orbit, around 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. Around 60 days after launch, researchers will carry out tests to ensure that the instruments' operational modes and scientific data processing software are optimised and ready for use. Trial scientific observations will begin 150 days after launch, and 6 months after launch, routine operations will commence. These will last for at least three years.