How the cells inside us like to dance

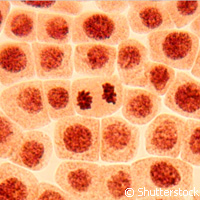

The exact science of how cells move about within the body has long been a mystery, but new research from an international team of scientists showing that cells like to move about as if part of a dance troop goes some way to filling in these blanks. The team, made up of researchers from Spain and the United States, investigated the physical forces that determine how cells migrate. Their findings, presented in the journal Nature Materials, show that these patterns of migration are both coordinated and chaotic, meaning that at first glance it can appear as if the cells are dancing as if in a ballroom, and at the same time like they are in a 'mosh pit'. With a boost from a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the 'Ideas' Thematic area of the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7), the study shows that in some cases the cells seem to battle with each other by pulling and pushing around as if in a chaotic dance, yet at the same time they all move together in a relatively coordinated and cooperative manner towards their intended direction. Until now scientists knew that cells could follow gradients of soluble chemical cues, called morphogens, which help to direct tissue development, or they could follow physical cues, such as adhesion to their surroundings. Fundamental studies of these and other mechanisms of cellular migration have focused on dissecting cell behaviour to solve the riddle of how migration occurs. Building on this existing knowledge, for this study the team moved things forward by looking at the cells at the group level, focusing on the forces cells exert upon their immediate neighbours. The data were collected using a measurement technology called Monolayer Stress Microscopy, which allowed the team to visualise the minute mechanical forces exerted at the junctions where individual cells are connected. Their studies led to discovery of a new phenomenon, which they named 'plithotaxis' - a term derived from the Greek word 'plithos' meaning a throng, swarm or a crowd. The crux of the study is that by studying the cells together, scientists could gain a much better understanding of their habits and behaviour. Groups of cells living in a single thin layer were analysed and the forces each cell experienced as it was navigating within the group were measured. 'If you studied a cell in isolation, you'd never be able to understand the behaviour of a cell in a crowd,' explains one of the researchers, Dhananjay Tambe from the Harvard School of Public Health. And the results certainly surprised the team, as researcher Corey Hardin from Massachusetts General Hospital explains: 'We thought that as cells are moving-say, to close a wound-that the underlying forces would be synchronized and smoothly changing so as to vary coherently across the crowd of cells, as in a minuet. Instead, we found the forces to vary tremendously, occurring in huge peaks and valleys across the monolayer. So the forces are not smooth and orderly at all; they are more like those in a 'mosh pit'-organised chaos with pushing and pulling in all directions at once, but collectively giving rise to motion in a given direction.' Collective cellular migration is essential for the functioning of the body. A good example is embryo formation: to form an embryo, cells must move collectively. Equally, to heal a wound, cells must move en masse to begin cell reparation. But understanding group cell migration is key for our understanding of cancer, where collective cellular migration has a negative effect on the body. Malignant cells can migrate to distant sites to invade other tissues and form new tumours. If scientists can get to the bottom of why collective cellular migration occurs they can better control conditions that are triggered by abnormal cell migration. For example, the study could lead to new breakthroughs in explaining how cancer cells migrate in the deadly process of metastasis. One of the study's authors, Xavier Trepat from the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) comments on the importance of study: 'We're beginning for the first time to see the forces and understand how they work when cells behave in large groups.' Scientists hope that these findings will help push forward knowledge of mechano-biology.For more information, please visit:Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC):http://www.pcb.ub.edu/homePCB/live/en/p369.aspNature Materials:http://www.nature.com/nmat/index.html

Countries

Spain, United States