Harnessing diet-microbiome-host interactions to fight colon cancer

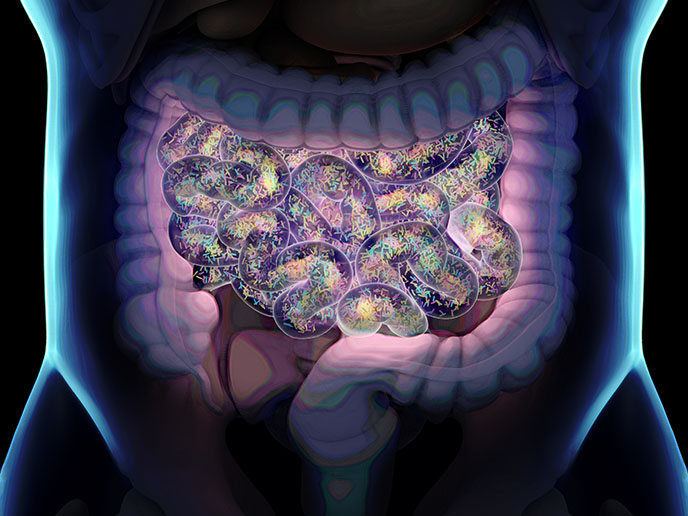

Studies(opens in new window) have shown that eating fruits and vegetables, rich in phytochemicals(opens in new window) and fibre, may reduce the risk of gastrointestinal diseases. But most beneficial nutrients are resistant to the stomach’s acidic conditions and so the antioxidant chemical compounds, called polyphenols, reach the colon almost intact. When polyphenols are exposed to gut bacteria and enzymes released by microorganisms, they are transformed into gut microbial metabolites. It is these metabolites in the colonic region that may affect cells in the gut, helping prevent gastrointestinal diseases. This leads to an intriguing question – are the protective effects of polyphenols due to their native compounds or their metabolites? The EU-supported TRIANGLE project set out to investigate the mechanisms by which diet-derived metabolites interact with the colon using human colon organoids/tumoroids. “Our findings reinforce the idea that metabolites play a pivotal role in improving gut health,” says Josep Rubert, Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow from the University of Trento(opens in new window). “The goal is to learn the language of gut-derived compounds to discover if they could serve as a Rosetta Stone(opens in new window) to promote gut health. I think we are on the right path.”

The value of organoids

Most dietary phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, display cancer-prevention activities in animals and humans, without significantly damaging healthy cells. A recent study(opens in new window) concluded that the lowest risk of cancer is observed when people consume 600 g/day of fruit and vegetables. But the evidence regarding polyphenols’ anticancer credentials is mixed. This may be due to the combination of polyphenols administered, the effects of accompanying compounds (generally fibre), the impact of gut microbiota or the type of cancer investigated. So, TRIANGLE used gastrointestinal tract models to investigate the processes by which phytochemicals, particularly polyphenols and fibres, are transformed into gut microbial metabolites. This allowed the team to identify promising protective gut microbial metabolites. These metabolites were then introduced to organoids (and tumoroids) – organic 3D tissue replicas – singly or in combination. The human colon organoid responses were measured using mass spectrometry(opens in new window) and 3D imaging techniques using automatic confocal microscopes. TRIANGLE found evidence that metabolites released from the microbial metabolism of flavan-3-ols(opens in new window) in the distal gastrointestinal tract may promote programmed cell death (apoptosis) inhibiting cancer, while promoting gut health. “Using intestinal organoids as models for colorectal cancer (CRC) and mass spectrometry to document the impact of diet-derived metabolites on organoids/tumoroids, has hardly been done before,” adds Rubert. “This gave us a lot of insight into metabolic processes.”

Towards prevention

CRC is the second most common cause of cancer-related death in Europe. It is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females. Forecasts(opens in new window) show that incidences of CRC are expected to increase by 60 %, to over 2.2 million new cases and 1.1 million deaths by 2030, due to an ageing population and the increased adoption of ‘Western’ diets and lifestyles. TRIANGLE, and similar projects, could improve individual health by identifying the type and quantity of microbial metabolites needed to prevent CRC, or other gastrointestinal diseases. “With more knowledge we could identify preventive actions, such as diet recommendations and the creation of precision prebiotics and probiotics(opens in new window). This would reduce disease prevalence and improve health outcomes, while lowering healthcare costs,” explains Rubert. The team plans to validate their findings using animal models or dietary interventional studies, while also further understanding the gut microbial metabolite differences between healthy donors and CRC patients.