Analysing the influence of climate on cultural change

The transition around 11 700 years from the Pleistocene to our current Holocene epoch is widely seen as representing an irreversible change in the climate system. This of course has relevance today, with growing fears that we are approaching our own climate tipping point. “The transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene was one from really rather cold and variable to fairly warm and stable,” explains CLIOARCH(opens in new window) project investigator Felix Riede from Aarhus University(opens in new window) in Denmark. “While this is not directly comparable to our current situation, there are lessons there in terms of human impacts and responses. In many ways, it’s the rate of change that is more critical than whether it’s warm or cold.”

Factors driving human expansion

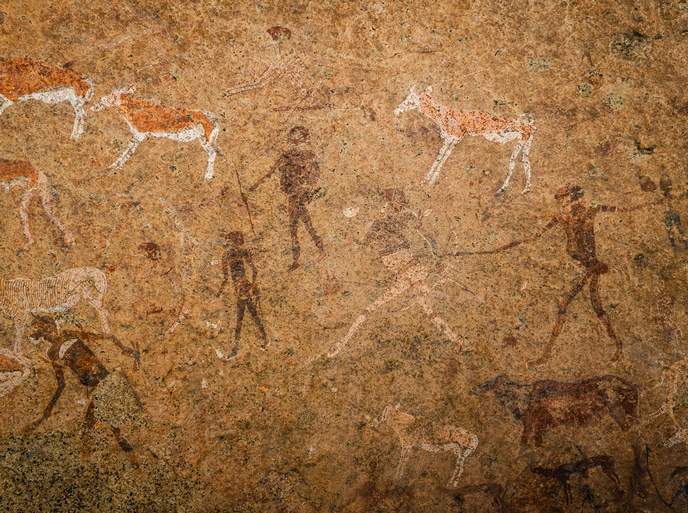

Taking this as the starting point, CLIOARCH, supported by the European Research Council(opens in new window), set out to examine the degree to which human civilisational change was influenced by climatic and environmental forces. The project focused on the five millennia from 15 000 to 11 000 years ago. CLIOARCH collected huge amounts of data from this period and transformed artefact images into statistical representations of their shape. These were then analysed using powerful new statistical tools. The project next developed climate models for this period, together with project partners at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology(opens in new window) in Hamburg. The aim was to identify climatic parameters beyond temperature and precipitation that may have been important for people in the past. The team also conducted excavations in Denmark and Germany. “We found an artefact bearing the earliest traces of blue mineral pigment in Europe,” says Riede. “This finding, alongside others such as the early sourcing of amber which we investigated at another site, really show that the hunger for very specific rare resources may have driven human expansion at this time.”

Defining climatic niche spaces

Overall, the project’s findings suggest that most human cultures at this time had a ‘spacious niche’ (referring to their ability to inhabit and shape a wide variety of environments) and could have occupied much of Europe except during the harshest climatic downturns. “The reasons why they did not do so have to do with their search for very specific resources, major geographic corridors, cultural preferences, and likely chance,” adds Riede. “These were the key hypotheses we pursued in CLIOARCH.” The project also demonstrated the efficacy of new digital methods to analyse cultural artefacts and was able to concisely define climatic niche spaces of early hunter-gatherers from this time.

Contemporary discussions about climate and culture

The project’s findings could also feed into contemporary discussions about climate and cultural change. The CLIOARCH project team has contributed to a major ICOMOS(opens in new window) paper on heritage and climate change, where it argues that the past may be seen as both an important parable but moreover also as a form of ‘solution archive’. “If we want to make evidence-based climate policy, then the past is where we can observe how human societies have actually responded to all sorts of climatic changes,” notes Riede. The project has also published papers(opens in new window) in peer-reviewed journals such as PLOS One, which often influence the drafting of major efforts such as Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports. “We have also contributed to museum exhibitions, published popular science papers, and presented our results to future generations through teaching,” says Riede. “None of these pathways should be underestimated in their eventual impact.”