Network tool can help to clean up space junk

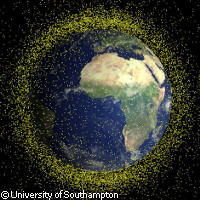

Scientists in the UK have used network theory to identify which objects in orbit around Earth are most in need of removal. Their mathematical tool shows the links between known pieces of space debris and pinpoints those with the greatest number of links to other objects. Targeting these highly-linked objects will significantly facilitate the planning of space clean-up. Space debris, also called 'orbital debris' or 'space junk', refers to man-made objects in orbit that do not serve a useful purpose. Some of the more interesting objects include a lost camera, wrench and toothbrush, as well as garbage jettisoned by cosmonauts; however, because of where they were released, these objects, for the most part re-enter the Earth's atmosphere within a short time and aren't major contributors to the space-debris problem. Rather, explosions of rocket upper stages have caused serious problems by releasing an estimated 100 tonnes of fragments that remain in low orbit. In addition to these explosion fragments, redundant satellites, satellite-associated objects (such as bolts) and used rocket bodies remain in orbit and pose a real threat to functioning satellites and spacecraft. Many smaller pieces travel at speeds of up to 10 km per second and have the potential to cause real damage, creating still more debris in the process (this scenario is referred to as the Kessler Syndrome). Space debris is one of the greatest hazards faced by space missions, including one to the Hubble Space Telescope scheduled for today (it has been postponed). At an altitude of just under 600 km, the telescope is in a fairly littered environment and there is a risk that the maintenance mission will face a catastrophic impact; accordingly, mitigating measures have been planned. The International Space Station, because of the very real risk of collision, has been armoured to protect itself from these high-velocity objects. Making plans to 'clean up' the debris is complicated by the fact that the number of objects is ever increasing, due to both the launch of new satellites and collisions between existing objects. Effective planning relies on scientists being able to identify those objects most at risk of collision. Rebecca Newland of the University of Southampton in the UK, together with a team led by Dr Hugh Lewis, created a mathematical network model that ranks objects according to the risk they pose so that they may be selected for removal from orbit. The researchers sought to establish how many potential links each known object has with other objects. 'The space debris environment can be thought of as a network in which the pieces of debris are connected if there is a possibility of them colliding,' explained Ms Newland. 'Once a network has been built, it can be analysed to identify objects that are important to the overall structure of the network.' She added, 'To destroy a network, it would be necessary to identify and remove those key objects, in the same way that targeting highly connected routers for removal could cripple the Internet.' Ms Newland explained that the network model runs simulations to predict future space environments, based on statistics from databases on objects currently in orbit such as those kept by NASA and the European Space Agency. 'We plan to further develop the tool by adding in more details about the objects, such as their mass, which is very important,' she said. 'The model now creates statistics-based projections for the space environment 200 years from now. If we have more data, especially on the mass of the debris, and more up-to-date information on where the objects are, the model can make better predictions.' The new tool, presented in Glasgow at the 59th International Astronautical Congress last week by Dr Lewis, has the potential to help slow down the production of space debris, effectively reducing the risk these objects pose to spacecraft and astronauts alike.

Countries

United Kingdom