Fossils reveal pre-Cambrian microbes, helping to solve Darwin's 150-year-old dilemma

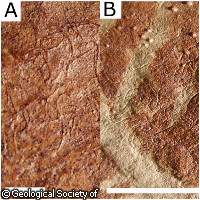

One hundred and fifty years after the publication of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species, scientists in the UK have used new techniques to uncover pre-Cambrian fossils on rocks examined by Darwin's contemporary, John W. Salter, in the 1850s. The findings, which are published in the Journal of the Geological Society, represent further evidence for life before the 'Cambrian explosion', a period of sudden and rapid species diversity. Darwin's 1859 publication, which explains how life evolves gradually over millions of years, was based on a relatively sparse fossil record. At the time, the oldest animal fossils dated from the Cambrian period, around 540 million years ago. What troubled the biologist and came to be known as 'Darwin's Dilemma' was the absence of older fossils; the sudden appearance of many groups in the oldest known fossils lacked explanation. 'To the question of why we do not find rich fossiliferous deposits belonging to these [...] periods prior to the Cambrian system, I can give no satisfactory answer,' Darwin wrote. He was sure, however, that such fossils would eventually be found, noting, 'only a small portion of the world is known with accuracy'. The recent study, by Mr Richard Callow and Professor Martin Brasier of the University of Oxford in the UK, focused on a rock formation from Shropshire, England, known as the Longmyndian Supergroup. Geologist J.W. Salter, who studied samples from the region in the 1850s, suspected that hidden within the rocks was evidence of pre-Cambrian life. Unfortunately, he was able to identify only certain unusual markings which may have been left behind by organisms. 'We examined all of John Salter's original materials which he collected in the 1850s (in the British Geological Survey), some 19th century specimens in the Oxford University Museum and also the material collected by [contemporary paleontologists] McIlroy, Crimes and Pauley,' said Mr Callow. 'In addition to this we also visited localities in the Longmynd to study the rocks in context and to collect more materials for our own collections which we could study and apply modern techniques.' Mr Callow and Professor Brasier examined Salter's 'trace fossils' in more detail, and for the first time unveiled a wide variety of exceptionally preserved microscopic fossils. The fossils represent microbial life forms dating back to the Ediacaran period (between 542 million and 630 million years ago), which immediately precedes the Cambrian. The scientists examined the materials using traditional optical microscope observations (the fossil remains are typically not visible with the naked eye) and examination in a scanning electron microscope (SEM). 'We also studied 'thin sections' of the rocks, where a thin slice of the rock is made to make it transparent so that light can be shone through the rock to show internal features,' explained Mr Callow. SEM examination clarified the shape and morphology of some of the fossils, and energy-dispersive X-Ray spectroscopy (EDX) helped the researchers determine the chemical composition of the fossil remains. 'This allowed us to recognise that the fossils are preserved within three different styles of fossil preservation,' he said. The findings are significant from a number of perspectives, according to the authors. 'Firstly, the wide variety of fossil morphologies found by us suggests that a diverse array of different types of microbes may be present, including possibly bacteria, algae and even possibly fungi,' explained Mr Callow. For comparison, previously discovered pre-Cambrian fossils known as the Gunflint fossils are believed to be only simple bacterial fossils. The fossils were found to have been preserved in a number of ways: Some were compressed under layers of sediment until they formed a thin film of carbon residue on the surface of the rock; other preserved samples were three-dimensional and may have undergone permineralisation. Some were preserved as impressions and moulds within layers of sediment, appearing as sharp ridges, or as their equivalent negative impressions. This shows that 'conditions for organic fossil preservation in the Ediacaran appear to have been rather good, compared with younger rocks,' said Mr Callow. 'The fact that these rocks have retained some secrets for over 150 years is a particularly interesting point, and that the same rocks that Darwin identified as a solution to his 'dilemma' have, in fact, turned out to contain abundant evidence for microbial life in the pre-Cambrian.' The paleontologists are not certain how the microbes kept themselves alive, but they speculate that because the microbes lived in shallow marine environments, they may have survived either by converting light into energy (like plants do), or by converting organic substances into energy (as animals do). The microbes could be related to algae, fungi or any number of bacteria. The fact that the fossils date from immediately before the radiation of animal life in the Cambrian explosion is of particular interest, as this could help scientists to understand this important event. The importance of the trace fossils found in the Longmyndian Supergroup has been recognised since Salter's pioneering discoveries. The recent findings, revealing the secrets of the Longmyndian rocks and their exceptionally preserved fossils, provide an invaluable piece of Darwin's troubling puzzle and a source of inspiration for evolutionary biologists.

Countries

United Kingdom