Hi-tech anthropology techniques uncover early humans' nut-cracking habits

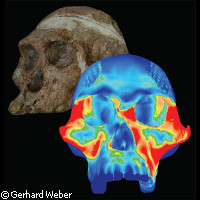

New EU-funded research sheds new light on how diet shaped the evolution of an early human-like species. Writing in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the scientists explain how the sturdy facial bones of Australopithecus africanus enabled it to crack into large nuts and seeds. This ability would have been extremely advantageous at times when other, softer foods were unavailable. EU support for the study came from EVAN ('European virtual anthropology network') which is financed through the Marie Curie (human resources and mobility) budget line of the Sixth Framework Programme (FP6). A. africanus lived in southern Africa over two million years ago. It has highly distinctive facial features, including large molar and premolar teeth covered with thick enamel, bony buttresses on the face and large markings for the attachment of the jaw muscles. Previous researchers have suggested that these features could have been important in chewing small, hard objects or chewing large amounts of different types of food. In the current study, the researchers used the latest technology to probe the matter further. First, Gerhard Weber's Virtual Anthropology team at the University of Vienna in Austria created an accurate, three-dimensional model of one of the few known A. africanus skulls. The precious fossil was scanned with computer tomography and virtual anthropology software was applied to remove plaster and draw on data from other fossils to fill in gaps. 'In this case we were lucky to have teeth available from a very similar other specimen so that we could reconstruct the edentulous face of 'Mrs Ples', as the fossil is called,' commented Professor Weber. The next challenge was to carry out a Finite Element Analysis (FEA), an engineering technique which examines how complex structures respond to stresses and strains caused by external loads. This work was led by a team at the University of Albany in the US. The results of all this work revealed that chewing 'either small objects or large volumes of food is unlikely to fully explain the evolution of facial form in this species'. In fact, the distinctive features of A. africanus are more likely to be an adaptation to 'the ingestion and initial preparation of large, mechanically protected food objects like large nuts and seeds,' the researchers conclude. Most nuts and seeds consist of a soft, nutritious core surrounded by a hard outer casing or shell. In times of plenty, A. africanus probably preferred softer foods that are gentler on the jaws, the researchers speculate. However, in times of famine, the ability to break into alternative sources of nutrition such as nuts and seeds could have been essential to survival. 'Given that australopiths experienced climates that were cooling and drying in the long term but which were variable in the short term, the need to periodically rely on fallback foods may have been critical,' the scientists explain. 'Australopith facial form is therefore likely to have been an ecologically significant adaptation.' The aim of the EVAN network is to pioneer the use of technological methods, such as those outlined above, in the field of anthropology and the study of human anatomy. Their findings could have applications in areas as diverse as medicine, prosthetics, forensics, biometrics and teaching. EVAN is also training young researchers in new and emerging techniques.