Do I know you?

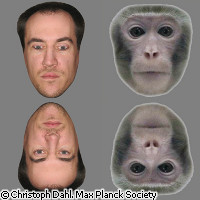

Both humans and macaque monkeys are able to recognise the faces of family and friends immediately by using holistic processing mechanisms. Scientists from Germany, Korea and the UK have discovered, however, that these mechanisms are significantly hindered when faces of the same species are inverted and when observing a different species. Findings from the study are published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences. The lead author of the study, Dr Christoph Dahl of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Germany, explained that as humans we become accustomed to the faces of other people from a very young age. Whether it be a father's long nose or an uncle's bushy eyebrows, 'we learn to recognise the small differences which contribute to an individual appearance'. Monkeys are similarly able to distinguish the identity of every member in a group just by processing information directly from an individual's face. But this shared ability of humans and monkeys is only true for individuals of the same kind. Recognition of conspecifics (members of the same species) is achieved in a somewhat holistic way; that is, we process the face as a perceptual whole rather than a series of individual features. Nevertheless, facial features, such as the mouth, nose and eyes as well the proportion of a face, are still important. 'Although we look at the eyes first, our neural functions still grasp the whole picture,' Dr Dahl pointed out. In the current study, the scientists used the so-called Thatcher illusion to study facial recognition processing in macaque monkeys and humans. In a 'thatcherised' image, the eyes and mouth are turned upside down. When these thatcherised faces are viewed the right way up, the changes in facial features are remarkably obvious. However they are barely noticeable when the face is turned upside down. 'The faces in which the eyes and the mouth were rotated 180 degrees look grotesque, but only if we see them the right side up. Upside-down, the differences between a normal face and a 'thatcherised' face are hardly recognisable,' explained co-author Dr Christian Wallraven from Korea University. In the experiment, 22 human observers and 3 male rhesus macaques were shown 40 digital colour pictures of neutral human and rhesus macaque faces. These faces were cut out and placed on a grey background. The stimulus set contained two manipulations: an upright normal, and an upright thatcherised. The entire images of both versions were then turned upside down (inverted normal, and inverted thatcherised. The result was that holistic processing mechanisms in both humans and monkeys allowed each to identify even the slightest of changes in facial feature arrangements when viewing faces that are upright, but the processing power was significantly reduced when a face was inverted 180 degrees. The scientists also discovered that the mechanisms fail to work completely with the faces of other species; neither the human nor macaque monkey participants in the study paid much attention to the extremely grotesque faces of the other species. 'It must have been of great advantage for us as well as for our next relatives, the monkeys, in the course of the evolution to recognise especially the faces of our kind and also to develop similar processing mechanisms,' concluded Dr Wallraven.

Countries

Germany, South Korea, United Kingdom