Pigment production, the 100,000-year-old way

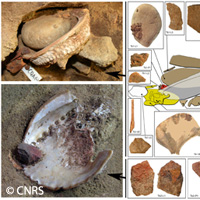

How humans source, combine and store substances that help drive both social and technology practices is a testament to how the human cognition has evolved immensely over thousands of years. Now an international team of scientists reveals how an ancient pigment factory produced and stored a liquefied ochre-rich mixture in Haliotis midae (abalone) shells. While the mixture's applications remain a mystery, the discovery could prove advantageous for decoration and skin protection. Presented in the journal Science, the findings represent the oldest historical evidence of pigment manufacturing and preservation, providing key insight into the planning behaviours of our prehistoric peers. Scientists from Australia, France, Norway and South Africa shed new light on how our prehistoric craftsmen developed innovative recipes and techniques 100,000 years ago or 60,000 years prior to the paintings of the Chauvet Cave, the earliest known cave paintings located in southern France. The researchers analysed painting remains preserved in large shells and on tools as old as 100,000 years in the Blombos Cave in South Africa. Researchers already recognised how prehistoric Europeans and Africans used red, yellow and black ochre, most often made up of iron oxides, for at least 20 millennia. But the question on the preparation and storage of the pigments remained... until now. Nearly 3 years ago, researchers recovered two sets of tools and ochre fragments, dating back 100,000 years, from Blombos Cave in South Africa. This maiden 'toolkit' comprised a large shell, what experts identify as being an abalone shell, covered in a five millimetre-thick layer of red ochre. It also contains a used pigment fragment and a quartzite flake (i.e. a rock made of quartz crystals). The shell's content was preserved by a pebble showing percussion marks. A quartzite slab and quartz flakes that show pigment residues and traces of use as grinders or crushes form part of this 'kit'. The kit also comprises an elongated bone, most likely used to mix or apply the pigment, the shoulder blade of a seal and a herbivore's vertebra. A second toolkit consists of an abalone, with a layer of pigment inside. A tiny block of ochre-stained quartzite and a fragment of red mineral showing traces of abrasion and cuts are also included. In a statement, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), one of the study's participating research institutes, says the team succeeded in reproducing the recipes developed by prehistoric ancestors to produce their pigments by investigating the fragments of ochre and the residues found on the unearthed tools and shells. The researchers identified the deliberate use of three types of rocks containing high quantities of haematite and goethite, what experts say are two of the most common iron oxides. The ancient artisans made a pigment powder by one of two means: they either broke and crushed the rocks or they abraded them using quartzite grinders. They also identified the possible use of bone marrow as a binding agent, and found that the mixture was liquid. The pigments were mixed and stored in the shells. The team points out that the colouring pastes were used for the colouring of materials including skin and rock, their preservation and protection, and for the creation of medicines, food supplements and paintings.For more information, please visit:CNRS:http://www.cnrs.fr/Science: http://www.sciencemag.org/(opens in new window)

Countries

Australia, France, Norway, South Africa