Distorted bodies in Italian literature from the Renaissance to the 20th century: A history of representation of emotions

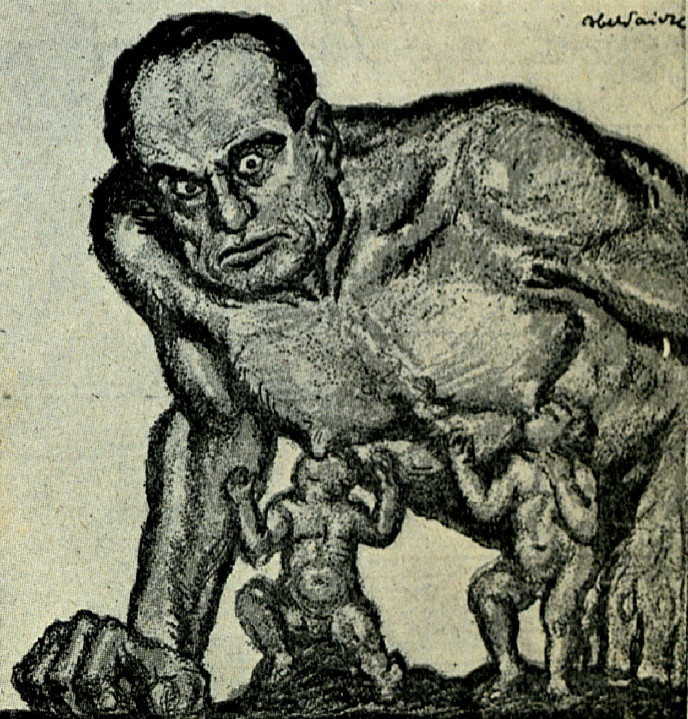

Caricature deforms the body and its social skin. By misshaping and exaggerating visual features, caricature provides an enhanced perception of facts and feelings, uncovers hidden aspects of reality and reveals unconventional knowledge about the world. Words can be distorted too Extensive studies of caricature have been undertaken since it became popular in the 16th and 17th centuries as a medium to ridicule public figures and politicians. Despite being a hybrid between visual and verbal codes, the textual dimension of caricature has been neglected. Researchers at the Queen Mary University of London have started to redress this balance and “emphasised that in literary texts there are descriptions of the human figure based on distortion, deformation, exaggeration of features and traits,” says Dr Paolo Gervasi, coordinator of the EU-funded Marie Curie project MISWORD. “They function exactly like visual caricatures, and therefore can be defined as ‘literary caricatures’,” he continues. Using the analogy and overlap between these verbal portraits and visual caricatures, Dr Gervasi has built a theory to describe this literary phenomenon, and to trace a history of the presence of caricatures in Italian literature from the Renaissance to the 20th century. Two very notable verbal caricatures One very suggestive example of how caricature represents an instrument of demystification of reality, a divergent possibility of representation is when Michelangelo describes himself as ugly, toothless, sick, deformed. “In so doing he destroys the mask of the idealised self-fashioning of the Renaissance artist,” explains Dr Gervasi. Michelangelo also defines his works of art as ‘scribbles’ and ‘puppets’, forcing us to think of a deformed David, a ridiculous Sistine Chapel. “Many centuries later, when caricaturists and writers represent Mussolini as a degraded, bestial, altered body, they are doing substantially the same thing,” continues Dr Gervasi. Writers deconstruct the conventional modalities of representation, showing that there is a reality in conflict with the official one. Both examples are representations of emotional projections onto the figures represented. “You can read the emotional and psychic state of the artist: the social frustration of Michelangelo, the anger and aggression of anti-fascist artists.” Evolution of the study into a European atlas of emotional forms MISWORD found that caricature is not the progressive and enlightened tool they had in mind at first, but a very ambiguous emotional device. The answer to the controversial task of defining caricature was to restrict the field of research to a specific historical period, Italy’s fascist period. “This has helped me greatly to overcome the difficulties of definition and framing. The general problem has taken on a more concrete form, and in the concrete, it has been possible to account for the complexity,” the coordinator concludes. Dr Gervasi would like to try and build a method to identify how the representation of the human body is linked to emotions, and how their representation is influenced by different social and political historical contexts. The dream is to be able to build a sort of European atlas of emotional forms. The MISWORD study has helped to understand the underground emotions that shake a society, and how emotional conflicts are processed, managed and represented. This is of great relevance for the present, arguably one of the most emotionally saturated epochs in history.