Tracing Old Norse and Latin in medieval manuscripts

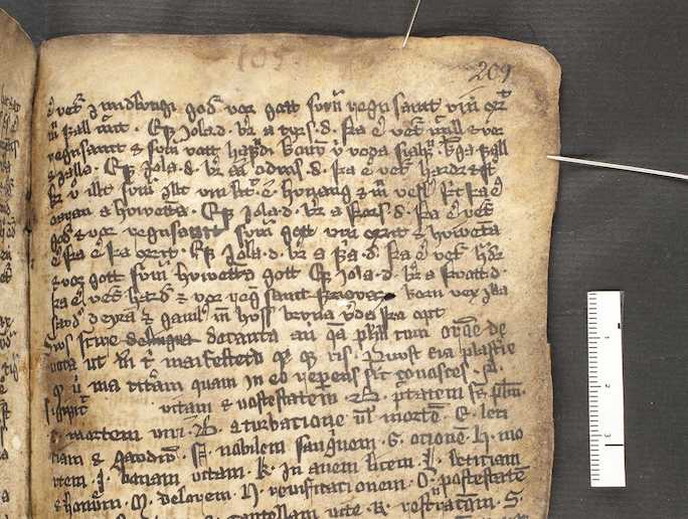

The use of Latin in medieval Iceland and Norway has long been ignored, mainly the result of nationalistic efforts to establish the two countries as being independent from the European tradition. However, this is slowly starting to change, with researchers continuing to discover the important role Latin played in a range of contexts. For example, Latin was influential in the production and transmission of texts and in various liturgical uses. There is even evidence of an intertextual relationship between many Latin and Old Norse texts. The EU-funded Invisibilia project, which was undertaken with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme(opens in new window), wants to tell you more about how well medieval Icelanders and Norwegians knew Latin as a second language. “Latin is a pervasive element in Old Norse manuscripts,” says Ms Astrid Marner, the Invisibilia project’s primary researcher. “The two linguistic components are mutually dependent and relate closely to a given manuscript’s individual purpose, use and history.” By tracing the Latin components of manuscripts, Marner is able to produce essential texts, which are then catalogued, digitised and made available via the project website(opens in new window). “The result of this effort will be a better understanding of the intellectual lives of people living in the Middle Ages,” says Marner. Out of small fragments comes a big discovery Using manuscript fragments, parchment slips, notes scribbled in margins, and references to lost works, the project is showing who knew Latin, how they used it, and how it interacted with their native tongue. Specifically, Marner relied on the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collections(opens in new window), which contain nearly 90 % of all existing Old Norse-Icelandic manuscripts. Although many of the entities found were too short or corrupt to be reliably identified, Marner did investigate 400 of the 629 relevant manuscripts found in the collection. Out of these, 125 (31 %) contained Latin text, two thirds of which had not previously been catalogued as containing Latin. Although these texts were overwhelmingly Christian in nature, they were found in manuscripts containing material of all types. According to Marner, the most important result of this work was the discovery of a mantic alphabet in a manuscript called AM 624 4to(opens in new window). “This is the only known instance of such writing from the medieval north, which indicates a connection to English traditions,” Marner says. “This manuscript, which was written by a scribe who clearly knew little or no Latin, is an important witness to the Latinity in late medieval Iceland.” More discoveries to be made Even though the project itself is now officially closed, with over 300 more manuscripts remaining unchecked, there is clearly more work to be done. “In addition to providing essential tools and texts for scholars of Old Norse and medieval Latin, Invisibilia has shed new light on the use of a lingua franca in a vernacular environment previously regarded as monolingual,” adds Marner. “But there’s more work to do and certainly more discoveries to be made.”