Are sleepless nights really harmful for health?

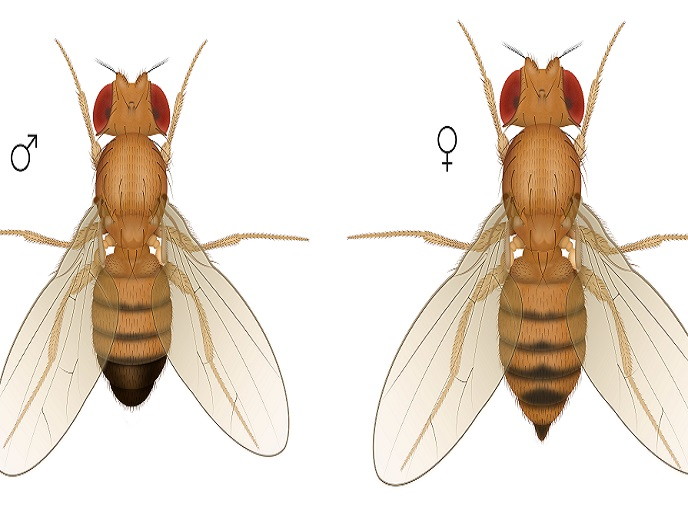

Sleep is universal throughout the animal kingdom. Most species devote a significant part of their day to sleep despite the risk from predators and time away from productive exploits such as feeding or breeding. It’s commonly held that sleep is under the control of two processes, a circadian or daily cycle and a homeostatic component, whereby the organism maintains internal conditions despite fluctuations externally. The EU-funded SEX_FIGHT_SLEEP project hosted at Imperial College London(opens in new window) tested long-standing assumptions about sleep function and regulation. “In particular, we wanted to test two aspects of sleep in a more quantitative and evolutionary sound way, using Drosophila melanogaster (the vinegar fruit fly) as an animal model,” explains Giorgio F. Gilestro, project coordinator. Scientists’ ingenuity helps them wake up to other options “We designed experiments that interfered with sleep regulation by manipulating social interaction,” outlines Esteban Beckwith, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow, and Quentin Geissmann, a then PhD student in the laboratory. A second question tackled the function of sleep, so the researchers looked at whether sleep serves a vital function in the way food does. The team describes the second part of the investigation as “putting forward a very daring and challenging hypothesis.” That sleep is not a vital necessity and does not serve a vital function is indeed a departure from the normally held beliefs regarding sleep deprivation. For the first time ever, they showed that sleepless animals exist and that chronic sleep deprivation is not lethal in Drosophila. SEX_FIGHT_SLEEP found that sleep deprivation that results from a forced male-male interaction leads to what is known as a ‘sleep rebound’, that is the urge to rest and recover lost sleep. However, flies that were kept awake all night through sexual arousal completely forego sleep rebound. They do not seem to need to recover the sleep they have lost. “This suggests that sleep deprivation is not just a quantitative manipulation but a qualitative one too – it is important not just how long we stay awake, but also how and for what!,” states Beckwith. Swarms of flies cause much media buzz The work with literally thousands of flies received wide attention and was featured in media such as the article(opens in new window) in eLIFE, The New York Times(opens in new window), the Public Broadcasting Service(opens in new window) and the BBC(opens in new window). Also, Imperial College London issued a press release(opens in new window) and published a video(opens in new window). “We wanted to perform sleep deprivation in a fully automated way,” outlines Gilestro. Building the technical infrastructure for the work was a project by itself. “Some of the problems were indeed totally unexpected, such as the influence of weather on the machines we were using for our analysis,” Gilestro recalls. “Also, working in summer was more difficult because our incubators couldn’t cope with the heat generated by the machines we were using (about 100 Raspberry Pi Computers),” Gilestro describes graphically. The team are now very interested in rebound sleep. Beckwith sums up with a vision of future research: “In particular, I am interested in understanding whether rebound sleep is really needed by the organism to restore something that has been lost with sleep, or whether the consequences of a rebound are simply a way for the body to re-establish a biological drive.”