Apprentices from millions of years ago: how did our ancestors learn to make the tools to survive?

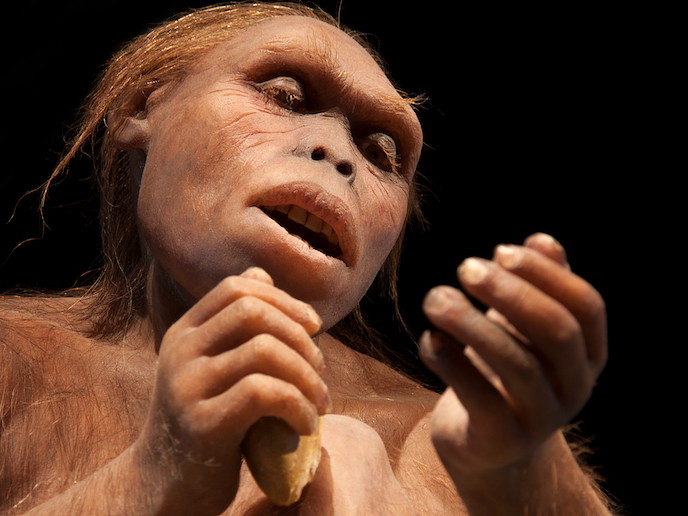

In prehistory our ancestors made tools from stone to get the meat off animal carcasses. Archaeologists have found lithic tools dating back as far as 2.6 million years ago and, thanks to the EU-funded project PREKARN, now know a little bit more about the skills required to make them and how those hominin societies taught each other the craft. Those who made lithic tools are known as ‘knappers’ and existed among the Homo habilis(opens in new window), who lived 2.1-1.5 million years ago and even as far back as the Australopithecus afarensis(opens in new window), a species who lived 3.9-2.9 million years ago in Africa. Research fellow Amèlia Bargalló, with support from the Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme, carried out an experiment to analyse the skills needed by knappers and to distinguish between novices and more experienced toolmakers. “By studying the prehistory knapping sequence, we see that there were knappers who were real experts and others where their tools contain a lot of mistakes,” says Bargalló. Fifteen people at University College London(opens in new window) took part in a first experiment to test PREKARN’s methodology. The project then asked 30 participants to knap as they did in prehistory.

Prehistoric techniques

Before they started, the researchers questioned the participants – other researchers in prehistory or students from different disciplines – to gauge their lithic knowledge. They then gave them nodules of Norfolk chert and Quarzite from the Utrillas as their hammerstone. The volunteers knapped using Palaeolithic methods and techniques while the researchers filmed them and collected all the lithic flake tools they produced for individual analysis. A database was created where the team used different statistical analysis to draw patterns for the tools produced to assign skill levels of the knappers. “Independently of their skill level, all the participants were able to produce a prehistoric simple stone tool (a flake) because Homo sapiens have good anatomic coordination and a complex brain capable of producing the first stone tools,” said Bargalló. Although Homo sapiens have more advanced brains than the extinct species that knapped, PREKARN’s results will help better analyse the lithic tools excavated over the years and discover more about the societies that made them. The results will help better label lithic tools on display in museums. By identifying skill levels of knappers, archaeologists will have more chance of identifying pieces produced by one prehistoric individual. This is one of the first times that researchers have analysed the technical characters of the stone tools. Until now, there have been few studies about how our ancestors learnt knapping and transmitted their knowledge. Bargalló shared the project’s results at the International Union of the Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences(opens in new window) conference, the European Society for the study of Human Evolution’s conference(opens in new window), with students during a school science week and in the newsletter of a Spanish scientific foundation, Atapuerca(opens in new window). “The next step is to connect this social learning and the way knowledge was passed on in prehistoric societies with the evolution of the brain,” says Bargalló.