High-tech solution to failing prostheses

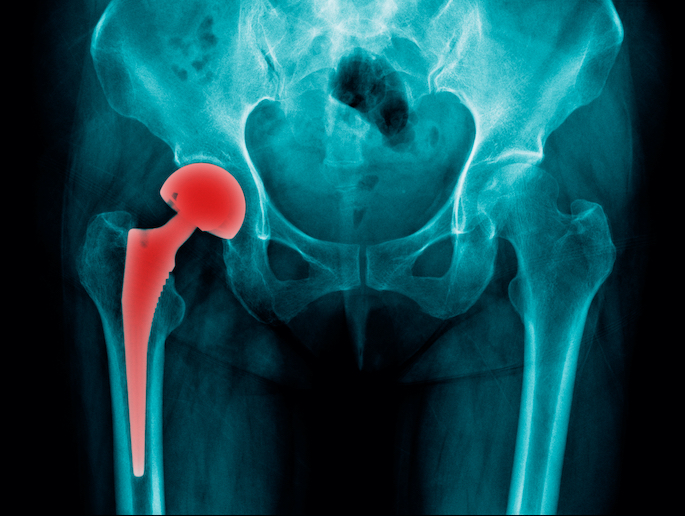

As our population ages, more medical attention is required to keep our bodies active and functional. Hip replacements for example are now a common medical procedure, with more than 1 million carried out worldwide every year. This trend is placing pressure on health services, not only in terms of operations, but also in terms of addressing problems when things go wrong. “An increasing number of patients are harmed due to malfunctioning medical implants,” explains Esther Punzón-Quijorna, Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow at the Jožef Stefan Institute(opens in new window) in Slovenia. “This can happen through friction in the body, which causes metallic particles from the prosthesis(opens in new window) to enter surrounding tissue. Or cells may recognise the implant as a foreign body and attack it. The degree to which a prosthetic hip can corrode can be shocking.” A complicating factor is that prostheses are not all made with the same material. The head of an artificial hip might be made of ceramic, while the rest might be titanium. Current diagnostic tools, such as X-ray scans and optical tissue microscopies, can help to identify that corrosion is happening, but they cannot adequately determine the content, size and nature of debris found in the body.

Detecting prosthesis degradation

The TissueMaps project was launched in recognition of the need for better diagnostic tools, to help identify which prosthesis component is causing the failure, and to what extent. This research was undertaken with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions(opens in new window) programme. “We applied particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE)(opens in new window), a cutting-edge microscopy technique to tissue samples obtained during surgery after a prosthesis failure,” adds Punzón-Quijorna. “PIXE enables us to ‘see’ things that we cannot see with ‘ordinary’ optical microscopy.” The technique helped the team to accurately map the distribution of particles from the prosthesis. This was achieved by taking advantage of the fact that the atoms that make up various elements are all different. “Titanium atoms are different from calcium atoms or iron atoms,” says Punzón-Quijorna. “Each atom has its own ‘fingerprint’, if you like. PIXE detects these ‘fingerprints’ by firing protons at atoms, which releases signature X-rays.” These X-rays can be collected and analysed, revealing the specific element causing contamination in the tissue.

Safer implants

The success of the TissueMaps project in mapping affected tissue could have a significant impact on the prostheses sector. For example, it could one day enable manufacturers to analyse prototypes and bring to market only those that can be shown to be safe. Conversely, prostheses that can be shown to be at particular risk of corrosion could be phased out. “Identifying implants at risk of failure could help to better deploy healthcare resources, and would therefore be much appreciated,” explains project team member Samo K. Fokter, senior consultant orthopaedic surgeon at the University Medical Centre Maribor(opens in new window), Slovenia. This mapping technology coincides with the emerging field of electronic implants, for example hearing aids that are connected to nerves. “This technology is coming,” notes TissueMaps project coordinator Primož Pelicon, head of department of low and medium energy physics at the Jožef Stefan Institute. “And when it does, it will be crucial for us to understand the reaction of the body to these implants. Will it leave the tissue intact, or cause allergic reactions? We need to know which materials are biocompatible.” In the meantime, the TissueMaps results have attracted interest from a hospital in Switzerland, which also wants to better understand why some prostheses fail.