Research deciphers how the brain retrieves contextual memories

Henry Molaison is arguably the most iconic case in neuroscience. When he had his brain hippocampus surgically removed to treat intractable epilepsy in the 1950s, science understanding of memory serendipitously received a tremendous boost. The patient lost the ability to form new memories, and the ability to complete tasks that required recall from long-term memory was severely impaired. His intelligence, namely the capacity to acquire new motor skills, remained intact, suggesting the hippocampus handles the recall of events known as episodic memories. “Episodic memories are autobiographical memories from specific events in our lives, like the place we celebrated our wedding. We most probably recall fine details about how the restaurant or garden looked like, or how the tables were arranged. Such memories tied to specific places, times and emotions are integral to our lives,” notes Koen Vervaeke, coordinator of the RSCmemory project that received funding under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme.

Memories flow out of hippocampus into other brain areas

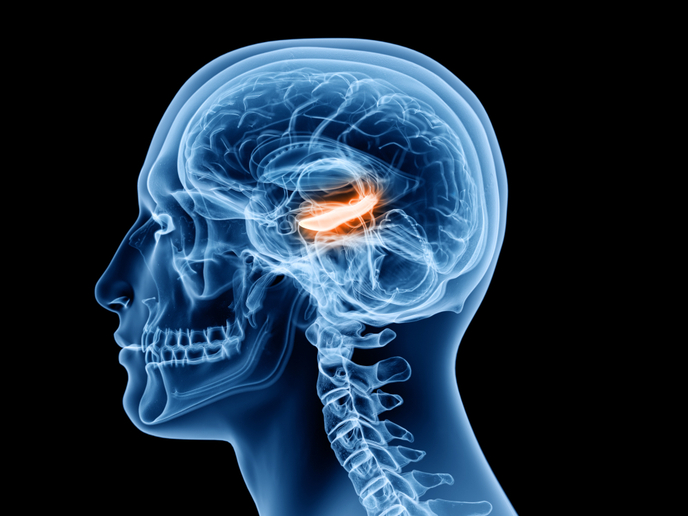

According to the classical model of memory encoding and retrieval, memories that initially reside on the hippocampus mature over time and flow out. The hippocampus influences neuron connections in the cortex, teaching it how to represent a memory. As the memory matures, the hippocampus expels it to reside in the cortex. “New studies suggest that a specific part of the cortex known as retrosplenial cortex(opens in new window) assumes a leading role in retrieving contextual memories. Any damage to this portion of the brain would severely impair the ability to search our memory and remember, for example, when we first heard a song that even though it is new, it sounds familiar,” explains Vervaeke. Research has also delineated the role the retrosplenial cortex plays in rodents’ ability to bind together different details of an event. It still remains unknown how neuronal ensembles in the retrosplenial cortex represent contextual memories.

Probing neuronal circuits necessary for contextual memory

RSCmemory has been one of the most ambitious attempts at finding the answer to this question. Researchers used novel optical techniques to monitor and control individual cell activity in mouse retrosplenial cortex. Importantly, the focus has been on tracking neurons exposed to different contextual information. Using two-photon microscopy and optogenetics, researchers activated neuronal responses in the retrosplenial cortex and showed that the representation of temporal information between the presented sensory stimuli depended on context. Neuronal responses differed depending on the identity of the preceding sensory stimulus. By recording hippocampal oscillations and simultaneously imaging neurons in the retrosplenial cortex, the team found that sensory stimuli not only evoke neuronal discharges in the retrosplenial cortex, but also synchronise neuronal oscillations in the hippocampus. Researchers also found that silencing neuronal activity in the medial septum nucleus(opens in new window) undermines the ability of the hippocampus to produce theta oscillations. This, in turn, decreases the overall number of neurons in the retrosplenial cortex that processes sensory and temporal information. The analysis of how neuronal circuits represent contextual memory is ongoing, but the data so far confirm that the retrosplenial cortex is indeed responsible for forming the basis for contextual memories. “Understanding how the retrosplenial cortex represents temporal context information could enable scientists to uncover the mechanisms that underpin disturbed memory processing during ageing,” notes Vervaeke. “Recent studies have shown that the retrosplenial cortex is one of the first brain areas that is damaged during the early stages of Alzheimer's disease.”