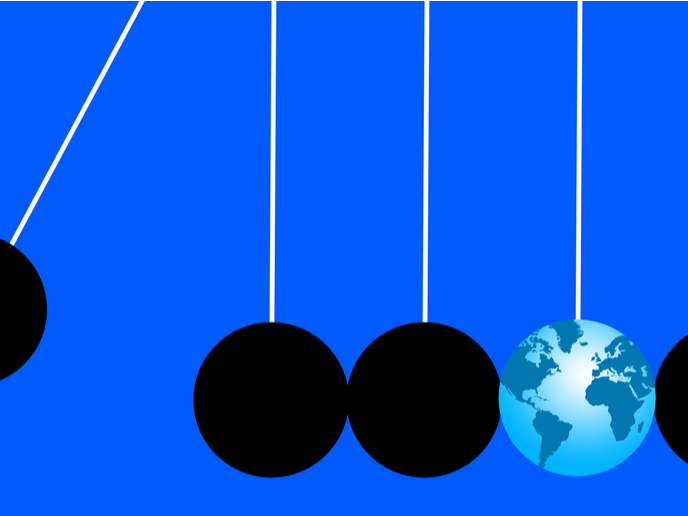

Beyond the climate tipping point: it’s not always so critical, but don’t relax

New research is giving us hope that crossing a tipping point might not be as disastrous for an Earth system as generally believed. Supported by the EU-funded TiPES project, the research shows that tipping of spatially heterogeneous systems such as ice sheets, lakes and forests does not always lead to irreversible changes in the whole system. In fact, the results might often be more subtle and less severe, as the study(opens in new window) published in the journal ‘Environmental Research Letters’ tells us.

Current models too simplistic

To date, many Earth systems have been shown to be susceptible to tipping, raising the spectre of irreparable catastrophes such as the disappearance of the Amazon rainforest, melting ice sheets and desertification. However, such predictions are typically based on simple conceptual models with only two alternative states, according to the study. The authors argue that in more complex models, tipping is often not as severe, causing, for example, only parts of an ice sheet to melt rather than the entire sheet in a single tipping event. In their study, the researchers investigate how conceptual models behave when spatial effects such as spatial transport and spatial heterogeneity are incorporated. They reveal that when such effects are added, the severity of the tipping event appears to strongly depend on the size and spatial heterogeneity of the system. In other words, when tipping happens in a large, spatially heterogeneous system, it is not as severe as a full tipping event and happens in smaller steps, causing restructuring in only part of the system. “On top of that, while part of the domain is still in its original state, restoration might also be easier and can happen more gradual: as climatic conditions would improve again, the spatial interface between states can move, slowly recovering the system,” the authors write. The study uses shallow lakes to illustrate the role that size and spatial heterogeneity play in ecological systems. In small lakes, there is limited heterogeneity. High nutrient concentrations can therefore cause excessive growth of algae, making these small lakes turbid. However, in a larger lake – where the system’s size makes it more heterogeneous – high nutrient concentrations might induce tipping in only part of the lake, leaving other parts clear. Passing a tipping point is therefore less severe in large lakes than in smaller ones. It even leaves open the possibility that the turbid areas of a large lake might clear up under the right conditions, such as if its nutrient pollution is reduced. Although the picture painted is not as dire as originally thought, it does not imply that climate tipping is not a concern. “I am still worried about tipping points. Because I can imagine critical things might happen especially as climate change persists. But I am not as worried that once we cross a tipping point, everything is going to hell immediately,” observes the TiPES (Tipping Points in the Earth System) study’s lead author Dr Robbin Bastiaansen of Utrecht University, the Netherlands, in a news item(opens in new window) posted on the ‘Mirage’ website. “I think it is going to be much more subtle than the kind of narrative that has been painted in some papers about planetary boundaries: that once we cross over one tipping point everything just collapses simultaneously. I don’t think that is the case.” For more information, please see: TiPES project website(opens in new window)