Peering into the characteristics of distant exoplanets

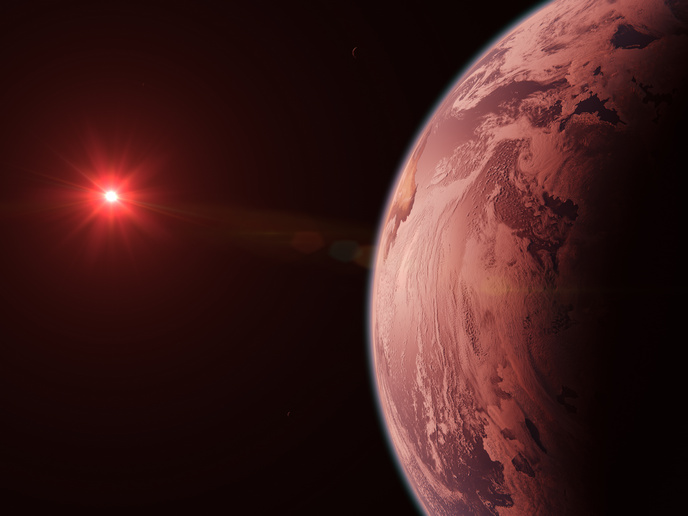

We have now discovered nearly 10 000 planets similar to Earth in distant galaxies. Recently, scientists discovered that small exoplanets are common around cool, red stars. This presents an opportunity to study their atmospheres to see whether future missions should seek life there. The EXOKLEIN project, funded by the European Research Council(opens in new window), created a holistic climate framework to interpret data from astronomical observations of smaller Earth-like planets. “The research is motivated by well-known facts in the exoplanet community, such as that M stars(opens in new window), which are somewhat smaller and cooler in temperature than our Sun, are more common than Sun-like stars in our Galaxy,” explains Kevin Heng(opens in new window), professor at the Munich University Observatory and EXOKLEIN project coordinator. Scientists wanting to study exoplanets via the transit method – when a planet passes between a star and the person observing it – are concerned with the relative size between the exoplanet and its star. This method is therefore more easily applied to large exoplanets orbiting Sun-like stars or small exoplanets orbiting smaller stars like M stars (also known as red dwarfs). EXOKLEIN focused its efforts on characterising the atmosphere, geochemistry and biosignatures of smaller exoplanets.

Virtual lab

To do this, the EXOKLEIN project created a virtual lab(opens in new window), a collection of software made freely available to the exoplanet community. “It is not just one piece of software, but a set of software that allows one to investigate different aspects of exoplanetary atmospheres: radiation, dynamics and chemistry,” notes Heng. Part of the vision and motivation is to force other researchers to make their computer software public and freely available to the community, so as to accelerate scientific progress, he adds.

Studying distant rock cycles

Another strand of the project research focused on the carbonate-silicate cycle, also known as the inorganic carbon cycle – the reaction between rock and water at warm temperatures. “We were interested in whether the composition of the rock (which is generally made up of a mixture of minerals) would influence the strength and behaviour of the cycle,” says Heng. The investigations under the EXOKLEIN project revealed that this is indeed the case. “This has the implication that, in order to understand how the cycle works on exoplanets in general, one has to have some knowledge of the rock composition on their surfaces,” Heng explains. The team also found that the composition of rock on an exoplanet is directly related to the abundance of refractory elements – those with high melting points – found in the star nearby. And as the research work evolved, the team realised geochemical outgassing was key to analysing distant climates, too. On Earth, volcanoes release gases that form part of the inorganic carbon cycle, for example.

Unexpected discoveries

In an unplanned exploration, Heng started investigating how starlight reflected from an atmosphere would look across wavelengths. Heng then discovered a mathematical solution to an old problem in planetary science, first posed in 1916 by Henry Norris Russell, which has major implications for interpreting data. “This was a major, unplanned outcome of the ERC project that I am very proud of,” he adds. Since small, rocky exoplanets are the future of the field, the EXOKLEIN results will be extremely relevant for how data are collected and interpreted by present and future telescopes.