Data-driven approach to risk assessment of micro and nanoplastics

Current experimental approaches to analysing the effects of micro and nanoplastics (MNPs) are not perfect. Different laboratories using different types of materials and different analytical equipment are producing different results. A systematic approach to develop and validate analytical methods and experimental systems that would deliver consistent and reliable results is urgently needed. This was the goal of PlasticsFatE(opens in new window), just one of the many projects funded by the European Union to limit the impact of plastics on our health and environment. “When PlasticsFatE started we knew that there were significant amounts of MNPs in the environment as a result of the wear and decomposition of larger plastics that society both uses and discards into the environment. “We had evidence that MNPs accumulated in different organisms, including humans, but we knew very little about the effects that they had on the human body,” says Mark Morrison(opens in new window), PlasticsFatE project coordinator and senior consultant with Optimat(opens in new window). “Our goal was to improve our understanding of the impacts of MNPs and associated additives and contaminants on human health,” adds Rudolf Reuther(opens in new window), scientific coordinator and founder of PlasticsFatE, and founder and head of Environmental Assessments(opens in new window), which conducts risk assessments of chemicals in the environment.

Testing current systems analysing micro and nanoplastics

The team identified and analysed a set of plastics that represent those we are most exposed to. These included PET, often used in drinks bottles, and PE, found in food packaging. They used both micro and nanoscale, and different shapes, to reflect the variety of forms of MNPs that might be having an impact on our health. “We characterised these MNPs using a variety of state-of-the-art equipment to be sure that we understood their physical and chemical properties – as these are what determine how MNPs interact with the living world,” explains Reuther. To test the consistency of current testing methods, PlasticsFatE subjected the MNPs to interlaboratory comparison studies. These comply with guidelines issued by international organisations, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

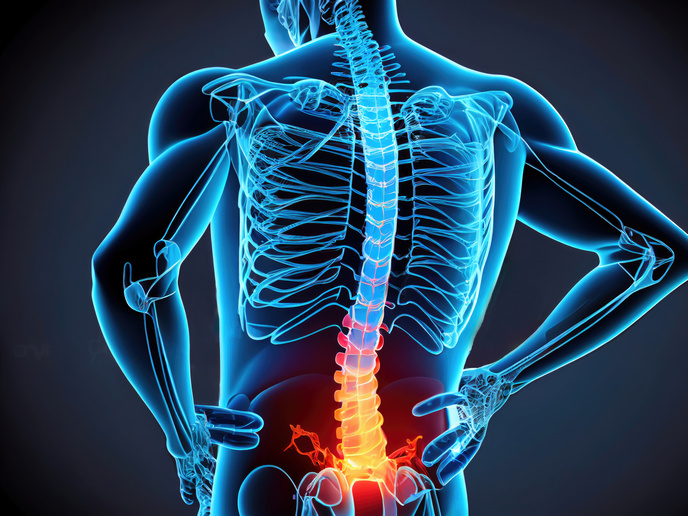

Impact of micro and nanoplastics on our bodies

While testing systems were evaluated, researchers also considered the impact on our bodies by taking uncontaminated MNPs, and those that had been contaminated with different chemicals, biomolecules and microbes. “We investigated what effects these had in a range of cell systems, from single-cell types to more complex multi-cell types that mimic the respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract, which are two major routes of human exposure to MNPs. The effects we studied included inflammation, immune responses and cell death,” says Morrison.

Micro and nanoplastics – potential impact on microbiome and antibiotic resistance

They found that over the exposure time investigated – hours to a few weeks – there was little effect of pure or pristine MNPs on the cell systems studied. “However, we found that MNPs can enter cells and cause changes in gene expression. We also found that MNPs can act as carriers for chemical and biological contaminants, taking these into cells,” notes Morrison. They also established that bacteria can bind to the surface of microplastics and, as a result, gene transfer between bacteria increased, which could have implications for the spread of antibiotic resistance. “We also found that MNPs can affect the composition of the microbiome in the gastrointestinal tract and that this was more marked in disease models. This could affect the ability of some people to digest and absorb nutrients from food,” Reuther adds.

A much-needed first step to assessing the role of micro and nanoplastics

The team feel it is vital to provide policymakers, regulators and other stakeholders with validated information, on which they can base decisions. “We have worked closely with our partners to produce a roadmap to describe future research on MNPs that we believe will address the remaining knowledge gaps. We have identified that longer-term studies on human health (over months and years) will be critical as will a more detailed investigation of whether MNPs have a stronger effect on people with underlying health problems,” concludes Morrison.