Universities at heart of regional knowledge economies, finds study

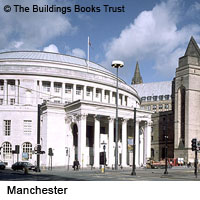

As prime producers of knowledge, universities play a central role in the rise and development of regional knowledge economies. But instilling the spirit of entrepreneurship and creating a viable technology transfer infrastructure between universities and industry, key obstacles to innovation remain. These are just some of the key findings from a recent study by the European University Association (EUA). Knowledge is seen to be globalised, defying borders, with 'knowledge workers' and companies becoming ever more mobile. Yet, for some time now, policy makers and experts have underlined the importance of the 'place' dimension for the growth of knowledge economies. They point to knowledge spill-over effects that have caused people and companies to locate closely to each other. This, they say, has spurred on the rise and development of regional knowledge economies, which have brought about significant economic benefits. In recognition of the importance of these clusters to their competitiveness, regional authorities are paying increasing attention to the knowledge economy and its needs in general, and the connectivity and support structures of clusters which have developed in the region in particular. The study looks at four European city-regions (Barcelona, Brno, Manchester and Øresund)) and finds that each of the key ingredients to an innovative region are being fostered. They include, among others, the growth of leading edge service and economic sectors; the promotion of the culture of knowledge, community investment, investment in education and highly-skilled labour forces. The regions are also seen to provide the perfect conditions for interaction between the key knowledge and innovation structures, namely: universities, government and businesses. In addition, the study points to how these regions have also successfully engaged the public in the processes of knowledge creation. Given this new context, each of these structures has come under increased scrutiny, not least universities. Questions are asked as to whether the knowledge produced in universities is the kind needed for the knowledge economy, and whether the channels through which this knowledge flows into production really meet expectations. According to the study, universities are fulfilling their role as prime producers of knowledge, covering not just scientific and technological development, but also social and cultural phenomena. The phenomenon of the knowledge economy, as well as the importance of regions, clusters and multi-actor interaction for knowledge development, were all identified, studied and explained first by university researchers and educators. Most importantly, universities educate and train graduates for the knowledge region. The study notes that all four knowledge regions examined pride themselves in offering an abundance and greater density of such graduates for their expanding knowledge economy than other competing regions. While this task is taken extremely seriously by the universities, with curricula and provisions being constantly reviewed, problems still arise, say the authors of the study. For instance, if skills are insufficient for the tasks they will be facing in their professions as innovators, researchers, technicians or managers, this may cause an imbalance. The authors found that some adjustments are still needed in order to prepare graduates for and adapt their skills to the challenges of the current and expanding regional knowledge economy. While many channels exist or are being established to improve the transition and adaptation of skills, the study found only one region had organised a regional skills partnership where different universities, training institutions and employers could discuss skills needs and provision. Another concern mentioned by the regional authorities interviewed is entrepreneurial mentality and skills, which are generally seen to be insufficiently developed, not only among students, but also among researchers. Many regional representatives commented that universities are not necessarily best suited for providing such entrepreneurial training. In some places, such training is thus co-designed by universities and businesses, supported by governmental regional agencies. In others, universities provide such courses but with business representatives as teachers. The most important task of universities, though, is the provision of a solid research base, and the study finds that in the regions under review, universities are fulfilling this role in all but two areas: research applicability and technology knowledge transfer. While keen to excel in research capacity and research quality, the study notes that many institutions tend to be more resistant to research applicability, since this is sometimes seen to undermine research quality. Paradoxically however, universities are eager to access the technology transfer infrastructure, but say that they do not have the means nor, for some aspects, the expertise to do so. In most of the institutions studied, technology transfer offices have been established in the last two or three years, but do not yet have enough staff to be able to confront the full range of tasks which they are to tackle. The study notes that the task of mobilising a particularly large part of the professorial community into becoming more interested in innovation and entrepreneurial activity is time-consuming and requires more human resources than most institutions have available. Moreover, in three out of the five countries in the four case studies, the majority of university researchers were still characterised (by university, business and government representatives) as being adverse to the idea of contributing directly to commercial innovation. But a lot is changing in a remarkably short time, say the study's authors. In all four places, an increasing number of professors are slowly becoming more open to, and interested in, innovation and cooperation with industry. With more and more positive examples of renowned basic researchers also being entrepreneurial - and enthusiastic about both types of research engagement - attitudes of the profession's more conservative representatives begin to change. For their part, national authorities are responding to the need for better technology transfer infrastructures, with many European governments having recently established university funds for innovation. These are either in the form of research funds for universities or university/business cooperation, or in the form of a whole 'third stream of funding'. This is allocated on the basis of a wider range of economically relevant engagement with non-academic partners. Such funding channels are intended to enhance the connectivity between universities and their environments and thus indirectly benefit regional knowledge networks. Although, regional authorities themselves do not generally exert great influence on university behaviour through financing mechanisms or 'hard' regulations, the study finds that they use their competences in a targeted manner to bring universities and businesses together. For example, aware of the importance of flexible space and high quality infrastructure for competitive research and innovation by universities, regional authorities often provide space and facilities to joint academic-business projects.