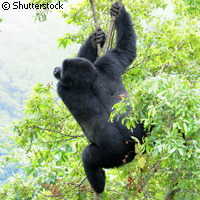

Getting to grips with gorillas' games

Just like human children, gorillas playing games of 'tag' will run away after hitting a playmate, new European research reveals. Furthermore, they run away for the same reason as humans do - to maintain their competitive advantage. The study, published in the journal Biology Letters, is the first to investigate whether animals respond to unfair situations in natural social settings. The research was supported in part by funds from the Leonardo da Vinci initiative, which is part of the EU's Lifelong Learning Programme. Previous research has investigated how various non-human species respond to unfairness, but these experiments were carried out in laboratories and tended to focus on the subjects who lost out. This study investigated videos of play fights that arose naturally in six social groups located in five zoos in Germany and Switzerland. The team set out to compare the chase-related behaviour of the hitters (i.e. the animals with the social advantage) and their playmates (those with the disadvantage). 'This study shows a new opportunistic side to apes,' commented Dr Marina Davila Ross of the Department of Psychology at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, one of the authors of the paper. 'Our findings on gorilla play show important similarities with the children's game of tag. Not only did the gorillas in our study hit their playmates and then run away chased by their playmates, but they also switched their roles when hit so the chaser became the chased and vice-versa.' 'Experimental research has already demonstrated that animals with the disadvantage in an unfair situation show an aversion to the unfairness, so with that knowledge and our own study we can conclude that humans are not unique in their ability to change their behaviour in social situations depending on whether they have the advantage or disadvantage in an unfair situation,' added Dr Davila Ross. Interestingly, the gorillas were less likely to run away immediately if they had only grabbed their playmate gently. According to the team, this suggests that 'great apes might perceive the roughness of their own behaviours towards others and the extent to which they violate a social situation and adjust their behaviours accordingly.' All of this raises the question of why animals engage in play-fighting in the first place. These games may provide a context in which animals can test responses to naturally occurring unfairness. They also provide an opportunity for individuals to interact with other group members in a rather unconstrained way. According to Dr Davila Ross, lessons learned in play fighting may help gorillas deal with real conflict. Playing the roles of both chaser and chased in the course of a game could help the animals to develop more refined and sophisticated communication skills. 'Our finding that gorillas respond to inequities during play fights provides, to our knowledge, first empirical support that animals playfully explore the ramifications of inequities,' the researchers conclude. 'Further research is needed to assess inequities during natural social interactions in non-human species, research that is likely to enhance our knowledge on the evolution of social competitiveness, fairness and morality in humans.' Also participating in the study were Edwin van Leeuwen of the Free University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands and the University of Portsmouth, and Elke Zimmerman of the University of Veterinary Medicine Hanover in Germany.

Countries

Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom