Trapped in time: mite's prehistoric piggyback ride on spider

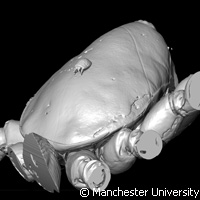

A team of scientists from Germany and the United Kingdom has successfully produced 3D images of a prehistoric mite as it grabbed a piggyback ride on a 50-million-year-old spider. The mite, who was just 176 micrometres long and barely visible to the naked eye, was trapped inside Baltic amber (fossil tree resin) and is the smallest arthropod fossil ever to be scanned using X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanning techniques. Writing in the journal Biology Letters, the team also explain that it would have taken 50 million years for these mites to evolve phoretic behaviour. This occurs when - without being a parasite - one animal clings to another to ensure movement from place to place, or hitchhiking, animal kingdom style. The fact that the mite was preserved in amber significantly aided the scientists' work. The fossilised resin popularly used in jewellery is known for its ability to preserve organisms and the behaviour they were enacting at the time of their death with lifelike fidelity. The amber essentially freezes an organism 'in action'. However, this particular amber fossil offered the team a unique look into the past. 'Most amber fossils consist of individual insects or several insects together, but without unequivocal demonstrable evidence of direct interaction. The remarkable specimen we describe in this paper is the kind of find that occurs only once in say a hundred thousand specimens,' enthused one of the study authors, Dr David Penney from the University of Manchester. 'CT allowed us to digitally dissect the mite off the spider in order to reveal the important features on the underside of the mite required for identification. The specimen, which is extremely rare in the fossil record, is potentially the oldest record of the living family Histiostomatidae.' Another study author, Dr Richard Preziosi, also from the University of Manchester comments on the team's findings: 'Phoresy is where one organism uses another animal of a different species for transportation to a new environment. Such behaviour is common in several different groups today. The study of fossils such as the one we described can provide important clues as to how far back in geological time such behaviours evolved. The fact that we now have technology that was unavailable just a few years ago means we can now use a multidisciplinary approach to extract the most information possible from such tiny and awkwardly positioned fossils, which previously would have yielded little or no substantial scientific data.' Mites and their close cousins ticks are small arthropods that belong to the subclass Acari and the class Arachnida. Mites are known to cause several forms of allergic diseases such as hay fever, asthma and eczema and are known to aggravate atopic dermatitis. Mites like to frequent warm and humid locations such as beds. Study author Dr Jason Dunlop from Humboldt University in Berlin says: 'As everyone knows, mites are usually very small animals, and even living ones are difficult to work with. Fossil mites are especially rare and the particular group to which this remarkable new amber specimen belongs has only been found a handful of times in the fossil record. Yet thanks to these new techniques, we could identify numerous important features as if we were looking at a modern animal under the scanning electron microscope.' Dr Jason Dunlop also expresses his delight that their work has contributed to 'breaking down the barriers between palaeontology and zoology even further'.For more information, please visit: Manchester University: http://www.manchester.ac.uk/(opens in new window)

Countries

United Kingdom