Key proteins in the brain provide early clues to Alzheimer’s disease

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not yet understood, but recent research shows the disease is identified by the accumulation of two proteins in the brain known as amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau. The CONNECT project, funded with the support of the EU’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions, aimed: “To identify the earliest brain changes we can measure that indicate the accumulation of these proteins. We can then use this information to predict who is more likely to progress to Alzheimer’s disease later on,” explains Heidi Jacobs, assistant professor at Maastricht University’s School for Mental Health and Neurosciences(opens in new window) in the Netherlands. Scientists now know these proteins accumulate in the brain 20-30 years before the first clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, confusion or disorientation, begin to appear. Autopsy data shows tau proteins start to accumulate around age 20 in a tiny region hidden in the brainstem known as the locus coeruleus, from the Latin for ‘blue spot’, as its pigmented cells show up coloured blue at autopsy. As people age, tau pathology progresses upwards to brain regions critical for memory functioning, Jacobs explains. On the other hand, around age 50-60, Aβ proteins start to accumulate, moving in the opposite direction. They start higher up in the cortex or outer layers of the brain and reach the brainstem during the advanced stages of the disease. Neuroscientists believe the two proteins interact, leading to detectable cognitive deficits, according to Jacobs. “Changes in the blue spot could presage cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s disease, but because of its location, the blue spot is difficult to measure using common imaging methods,” she explains.

Investigating the ‘blue spot’

Jacobs was previously a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston(opens in new window), United States (US), affiliated with Harvard Medical School, where a specific method was developed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualise the blue spot. “Using this method, we were able to measure its structural properties related to the amount of neurons,” Jacobs says. “It is here we see the very first consequences of accumulation of tau, even before there is any Aβ and before there are any clinical symptoms.” Using another advanced neuroimaging technology – positron emission tomography (PET) – using a radioactive tracer that lights up when it binds to those proteins in the brain, the team found that fewer neurons in the blue spot correlate with a higher presence of tau. “This was known from post-mortem studies but not shown before in live human brain scans,” Jacobs notes.

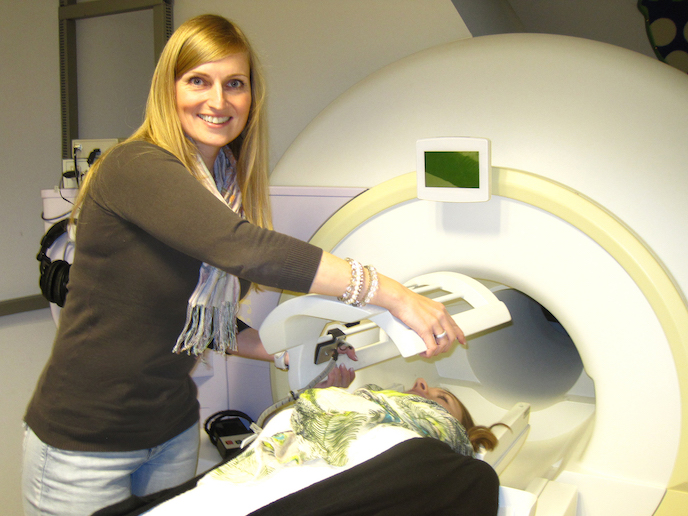

More sophisticated imaging

“As the disease progresses – when individuals exhibit increased Aβ as well or we can observe clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s – then these associations become stronger.” Individuals with worse blue spot integrity and minor Aβ pathology show faster memory decline over time than those with more neurons and less Aβ. “The two seem related,” she says. Cognitive performance data, including memory tests collected for over 10 years by the Harvard Aging Brain Study(opens in new window) in the US, were used to see how individuals declined over time. The cohort of 300 individuals aged 50-80 were all cognitively healthy at the start of the longitudinal study. The team is currently using Maastricht University’s high field MRI scanner which has a higher magnetic field than a regular scanner to zoom in on the blue spot and observe blue spot neuron density changes in individuals as young as 30. “The beauty is the combination of the two because PET tells us about the molecular nature of the brain while MRI tells us something about the brain structure and function,” Jacobs says.