To cut or not to cut: The case of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales

Throughout history, gauging and pre-empting the offence that language can cause has always been a struggle. Many literary works have found themselves at the centre of debates about whether their content was acceptable or unacceptable at a particular moment in history. To gain a better understanding of what kinds of literary content are censored and why, the EU-funded Censoring Chaucer project, with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSC) programme, examined censorship and celebration of obscenity in medieval and early modern copies of The Canterbury Tales(opens in new window). Specifically, the research looked at ‘sexual and scatological language and content’ explains MSC fellow and lead investigator Mary Flannery.

Putting Chaucer’s work under the microscope

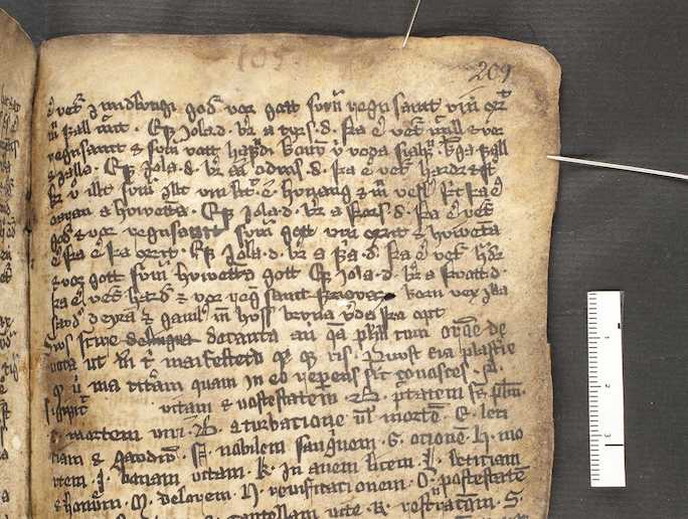

Written at the end of the 14th century, The Canterbury Tales is one of the most famous, and occasionally controversial, works of medieval literature. The author, Geoffrey Chaucer, sometimes called the ‘father of English poetry’, is a key figure in English literary history. “By uncovering the history of how his bawdy humour and obscene language were received in the first centuries after his death in 1400, we get a clearer sense of what factors determine what gets left in edgy texts and what gets removed,” notes Flannery. A key finding of the project is that across the 84 manuscripts and fragments of The Canterbury Tales that survive from the 15th century, there were different responses to Chaucer’s obscenity. “Some manuscripts leave out objectionable passages or replace objectionable words. Others elaborate on famous passages, such as the end of The Merchant’s Tale, where two characters have a sexual encounter in a pear tree,” highlights Flannery. In several manuscripts, scribes have added extra explicit descriptions of this encounter. But most manuscripts simply record these rude words and humorously indecent scenes with no comment and little variation whatsoever. “Therefore, we can’t make sweeping generalisations about how readers in this period responded to the sexual and scatological content of The Canterbury Tales.”

Overcoming challenges

“The biggest challenge of this project has been the issue of how to do justice to the individual manuscript and print copies of The Canterbury Tales while also keeping an eye on the larger story,” reports Flannery. This is because different copies have different kinds of evidence concerning the responses of individual scribes, readers, editors or publishers, or artists in the case of illustrated copies. To overcome this, Flannery pursued two parallel ‘streams’ of publications: more focused case studies on individual copies in the form of articles and book chapters, and the monograph that will form the final output of the project which will also trace the broad history of this issue over the past six centuries. These and others are listed on the fellow’s website(opens in new window). Moving forward, Flannery shares: “I have been awarded a 5-year grant by the Swiss National Science Foundation(opens in new window) to complete the history of Chaucer’s obscenity and its reception over the past 600 years.” The new project, ‘Canonicity, Obscenity, and the Making of Modern Chaucer’, builds on the results of Censoring Chaucer by focusing on how readers and publishers responded to Chaucer’s obscene language and content between 1700 and the present day.