How music shaped European views of Indigenous South Americans

Music is more than sound. It resonates not just in our ears, but impacts on our identities, beliefs and historical legacies. In Europe’s colonial history, it also played a role in cross-cultural interaction, influence and interpretation. Undertaken with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme(opens in new window), the Harmony on the Edge(opens in new window) project explored the effects of musical encounters between European and South American cultures during the Early Modern period (circa 1500-1800). “Unlike contemporary views, music at the time was not solely regarded as an art form – it was also seen as a science, a world view and a framework through which politics and social order could be reimagined,” says Amparo Fontaine, principal investigator of the Harmony on the Edge project. Through extensive archival research in France and Chile, among other countries, the project suggests that “encounters with South American music not only shaped European conceptions of the humanity and cultural traits of Indigenous populations but also prompted broader inquiries into human nature and human diversity.” Fontaine explains that these musical encounters contributed to fundamental questions about the origins of history, concepts of universality and the development of language – matters that became central to Enlightenment thinking. The role of music as a form of knowledge during this period was also addressed at an international conference(opens in new window) organised by the researcher.

Music as a mirror of the colonial mind

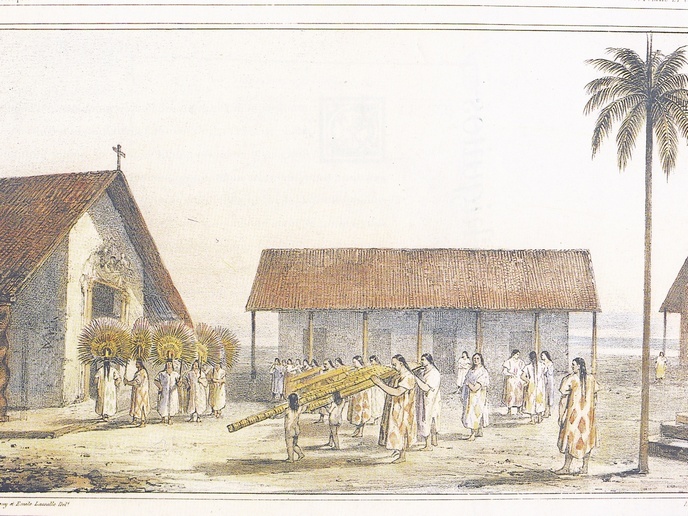

While previous research has often focused on the musical education programmes used by missionaries and the Catholic Church as tools for evangelisation and colonisation, Harmony on the Edge took a wider view of how Europeans interpreted Indigenous music. The study drew from accounts of natural philosophers, military personnel, colonial administrators and other travellers. Despite the diversity of sources and their aims, experiences and aesthetic sensibilities, they frequently referred to music in their writings about South America and recognised the musicality of Indigenous peoples. “At the same time, however, Indigenous music was often dismissed as mere noise – a term that carried strong political and moral implications. In contrast, the notion of harmony was rarely ascribed to these musical practices,” reveals Fontaine. The project highlights that notions of race and civilisation were built through sound. Europeans often interpreted specific instruments and bodily movements, such as dance or performance, as markers of cultural identity, using them to draw boundaries between the ‘civilised’ and the ‘savage’. A recurring theme across the project’s case studies is the idea that music was used to ‘domesticate’ Indigenous peoples, seen as a powerful tool to instil morality and Christian values. But music was also used to defend Indigenous ingenuity, sensibility and social organisation, as a medium to assert the shared humanity between themselves and Europeans.

Objects, instruments and traces of encounter

Harmony on the Edge highlights the varied interpretations of Indigenous soundscapes, tracing how musical instruments, eyewitness accounts and travel reports shaped European conceptions of the Americas. Material artefacts were a central part of the research, including those that were described, collected, studied or visually depicted. While Indigenous perspectives remain largely inaccessible – with sources being mostly European – certain objects and images offer traces of identifiable moments of exchange. Through examples ranging from the pan flute to a flute allegedly made of human bones, the project shows how music and musical encounters contributed to constructing ideas about civilisation, race and cultural otherness.