How a tiny grain of salt can help answer a big climate question

Winter westerlies, those prevailing winds that carry moisture from the Atlantic and into the Continent and beyond, are what shape winter weather across Europe and the Middle East. “Westerlies have a clear, marked influence on winter air temperature as they transport heat from oceans to land masses,” explains Emmanuel Guillerm(opens in new window), a researcher at the Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences(opens in new window). But how have winter westerlies changed over the last 12 000 years, and what does this mean for climate change? To find the answer to these questions, Guillerm, with the support of the EU-funded CROSSROADS project, took a deep dive to the bottom of the Dead Sea.

Accessing ancient thermometers

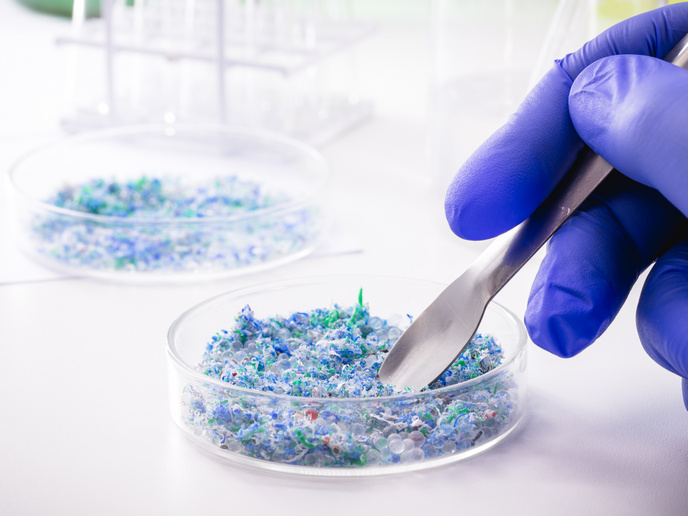

The Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions(opens in new window) project focused its work on the salt crystals that grow on the Dead Sea floor and trap tiny droplets of water. “These droplets act like miniature ancient thermometers, preserving the lake’s temperature at the moment they were sealed in,” notes Guillerm. “Because the Dead Sea mixes in winter, its deep-water temperature reflects the winter air temperature above it.” Guillerm also used the salinity of the droplets to reconstruct the evolution of both water volume and level.

Salt: preserving food – and climate information

By measuring the microscopic inclusions in salt deposits from a long sediment core from the centre of the Dead Sea, Guillerm and collaborators were able to build a long record of water level and winter temperatures. From this, they were able to see how westerlies behaved over the course of thousands of years. They also gained insight on recent trends in the Dead Sea. “Researchers have long known that the Dead Sea has experienced rapid warming, with water temperatures increasing by over 3 °C over the past four decades,” remarks Guillerm. Now, thanks to the work done by the CROSSROADS project, they also know why this is. “While half of this warming is due to the air warming, the rest is because of lake level decline caused by, for instance, water diversion for agriculture,” adds Guillerm. “This discovery implies that the Dead Sea will keep warming as it declines and as air temperature increases.” Another key finding was the existence of a positive feedback loop of shrinkage-warming in hypersaline lakes, which is crucial to understanding how large salt deposits formed in the geological past.

Understanding the past to anticipate the future

The project’s research will have a big impact on climate science. “We’ve shown that salt – one of the simplest minerals on Earth – can preserve climate information in a completely unique and quantitative way,” says Guillerm. “This opens the door to using salt deposits to tackle other climate puzzles, potentially reaching far deeper into Earth’s history.” According to Guillerm, this helps scientists better understand atmospheric circulation changes across geological timescales. “It also helps us anticipate how atmospheric circulation might behave in a rapidly warming world,” he adds. Guillerm says having access to such information will be particularly important for the Mediterranean and Middle East regions, both of which are at a high risk of water scarcity. “By understanding what drives changes in winter westerlies, we can better anticipate changes in moisture delivery and take steps to mitigate this risk,” he concludes.