Harnessing extreme ultraviolet light in tiny devices

The EU-funded X-PIC(opens in new window) project explored the extension of integrated photonics into a spectral region never exploited before, between the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) – a type of light that sits beyond ultraviolet – and soft X-rays sitting right next to EUV. The EUV light has wavelengths tens to hundreds of times shorter than visible light. “Existing technology does not work in this region, as matter promptly absorbs light over a hundred nanometres, or about one thousandth the diameter of a human hair,” explains Salvatore Stagira(opens in new window), professor in experimental physics at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, who coordinated the project. “However, this spectral region is very appealing because it allows imaging applications with extremely high spatial resolution as required nowadays by modern microelectronics manufacturing processes.” In this region, it is possible to generate the shortest artificial event – attosecond light pulses – the field behind the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics that explores extremely fast processes in matter. These pulses are as short as a few millionths of a billionth of a second. EUV-integrated photonics combines all the above-mentioned capabilities in a compact, miniaturised device.

Photonic technology breakthrough

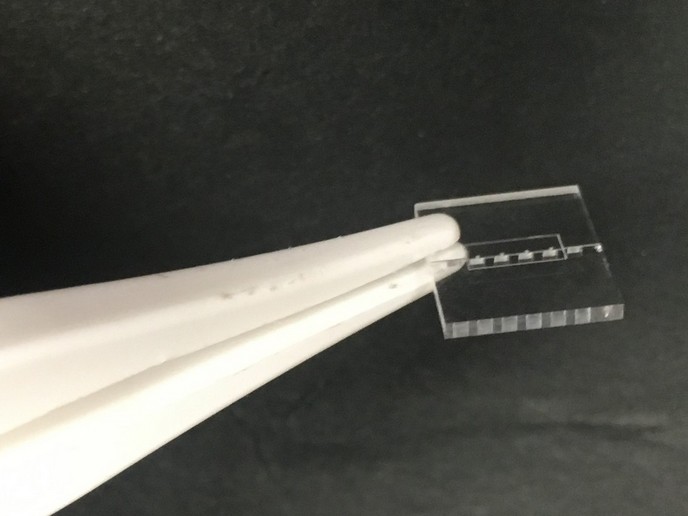

The X-PIC team demonstrated that it is possible to generate and manipulate coherent light pulses in the EUV spectral region inside a miniaturised platform. This was achieved in a small, fused silica slab using a technique called femtosecond laser irradiation followed by chemical etching (FLICE). Since EUV light cannot travel through most solid materials, the main idea was that it can instead be guided through an empty channel, with a diameter comparable to that of a human hair, via FLICE. Within this channel, an EUV light pulse is generated by the interaction of an intense and ultrashort IR laser pulse with a gas flowing through it. The device includes a network of microfluidic channels that feed the main channel with the gas. FLICE’s extreme flexibility enables the realisation of complex tri-dimensional empty structures in the device. The EUV pulse can then be separated from the IR laser pulse through additional empty channels. Finally, it can be exploited either inside the device or outside, depending on the application.

Towards the development of more complex devices

Stagira says that the major benefit of this outcome is the demonstration of a technology enabling the miniaturisation of an entire EUV beamline inside a small device a few millimetres long, while the usual EUV bulky beamlines extend over several metres. The beamline is the system that generates, transports, shapes and delivers EUV light. In the short term, this will mostly impact applications involving time-resolved spectroscopy(opens in new window). Long-term applications are foreseen in EUV metrology, photolithography(opens in new window), imaging and EUV quantum optics. “The X-PIC project merged two distinct technologies, the lab-on-chip approach, in which complex functionalities are performed inside a small device, with the generation of coherent EUV light pulses down to the attosecond regime,” concludes Stagira. “As a result, integrated photonics are entering a new realm.”