Researchers resolve cell division mystery

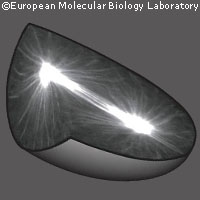

Researchers have worked out the mechanisms behind asymmetric cell division, a process which is important in embryonic development and the renewal of stem cells. The work, which was partly funded by a Marie Curie grant from the EU, is published in the journal Cell. When cells divide, the result is normally two identical daughter cells. However, in certain cases, for example during development, cell division can lead to two daughter cells with different properties, a process known as asymmetric cell division. In this latest piece of research, the scientists studied the embryo of a nematode worm called Caenorhabditis elegans. Soon after the egg cell has been fertilised, the C. elegans embryo undergoes its first cell division, and the two resulting cells are not identical. The cell splits into a large cell at the head end of the embryo, and a smaller cell at the tail end. The researchers knew that for this asymmetric division to work properly, the mitotic spindle, which separates the cell's chromosomes, had to be located towards the back of the egg, and not centrally. 'Just before cell division the mitotic spindle moves towards the posterior of the cell while oscillating up and down,' said François Nédélec of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). 'We wanted to find out the mechanisms of this motion and explore its properties.' Protein filaments called microtubules, which can grow and shrink according to their needs, are involved in getting the mitotic spindle to the right part of the cell. Dr Nédélec and his colleagues used computer simulations and microscopy to study the behaviour of the microtubules. They found that the microtubules grow until they touch the cell cortex, a structure which lies just beneath the plasma membrane and lines the cell. As soon as the microtubules touch the cortex, they start to shrink, and this shrinkage pulls the cortex inwards. 'How exactly this works we don't know yet,' commented Cleopatra Kozlowski, also of the EMBL. 'One possibility could be that part of the cortex holds on to the microtubule while it shortens, and so pulls on the whole spindle.'