Babies aware of social dominance by 10 months

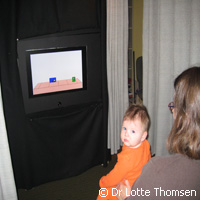

By the time they are 10 months old, babies are aware of social dominance and know that if 2 individuals come into conflict, the bigger one will likely prevail, new US-Danish research shows. The findings, published in the journal Science, suggest that we are either born with an understanding of social dominance or develop it at a very early age. The ability to identify individuals that are more dominant helps infants learn the structure of their social environment and guides them in their interactions with others. Dominance hierarchies giving certain individuals greater access to food, mates and other resources are found throughout the animal kingdom including in humans. According to the researchers, even toddlers form dominance hierarchies similar to those found in other primates. One factor linked to dominance in humans and animals alike is size. 'Traditional kings and chieftains sit on large, elevated thrones and wear elaborate crowns or robes that make them look bigger than they really are, and subordinates often bow or kneel to show respect to superior humans and gods,' explained the lead author of the paper, Lotte Thomsen, who is a research fellow in Harvard's Department of Psychology and assistant professor of psychology at the University of Copenhagen. 'Many animals, like birds and cats, will puff themselves up to look physically larger to an adversary, and prostrate themselves to demonstrate submission, like dogs do. Our work suggests that even with limited socialisation, preverbal human infants may understand such displays.' In this study, Professor Thomsen and her colleagues observed how youngsters aged 8 to 16 months reacted to simple cartoons featuring 2 blocks (1 large and 1 small) with simple faces (eyes and a mouth). In the clips, the two blocks approach one another from opposite sides of the screen until they meet in the middle, where they effectively block one another's progress. Next, one of the blocks bows and moves to the side, allowing the other block to proceed unimpeded. If infants understand the link between size and dominance, they will expect the small block to give way to the bigger block, and not vice versa. 'Since preverbal infants can't be interviewed, their experiences and expectations must be assessed by their behaviour. Infants tend to watch longer when something surprises them. So we can test hypotheses about what they expect by measuring how long they look at scenarios that either violate or confirm their expectations,' said Professor Thomsen. 'As predicted by our theory, the infants watched much longer when a large agent yielded to a smaller one.' In fact, when a small character in the cartoon gave way to a big one, the babies watched for an average of 12 seconds. However, when a large character allowed a small one to pass, the youngsters watched this surprising result for 20 seconds. Professor Thomsen comments: 'What we have shown is that even pre-verbal infants understand social dominance and use relative size as a cue for it. To put it simply, if a big and a small guy have goals that conflict, preverbal infants expect the big guy to win over the little guy.' Further studies revealed that the very youngest babies in the study, who were eight months old, did not appear to have expectations regarding the outcome of a social dominance conflict as depicted in the cartoon, and nine-month-olds had only some understanding of social dominance. However, test subjects aged 10 months and older had clearly acquired an awareness that size is an important factor in social dominance. 'A crucial task for the developing child is to learn the social structure of his or her world, in order to interact appropriately with kin and non-kin, friend and foe, superiors, inferiors and peers,' the researchers conclude. 'Our findings that preverbal infants mentally represent conflicting goals and social dominance between two agents suggest that just as infants possess early-developing mechanisms for learning about the physical world and the world of individual intentional agents, they also have early-developing representational resources tailored to understanding the social world, allowing infants to understand and learn the dominance structures that surround them.'For more information, please visit: Science:http://www.sciencemag.orgUniversity of Copenhagen:http://www.ku.dkHarvard University:http://www.harvard.edu

Countries

Denmark, United States