Collagen sequencing to shed light on fossilised past

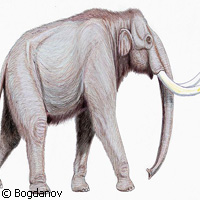

British scientists have come one step closer to identifying ancient fossils, following their recent extraction of protein from the bones of a 600,000-year-old mammoth. Presented in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, the research provides insight into how protein lasts for so many years in extremely old specimens. Bio-archaeologists from the Universities of York and Manchester used an ultra-high resolution mass spectrometer to generate an 85% complete collagen sequence for the West Runton Elephant, a Steppe Mammoth skeleton first discovered in the UK's Norfolk-based cliffs 11 years ago. They believe this is the oldest protein to be sequenced. The Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service in Norwich houses this near-complete skeleton believed by experts to be the most complete example of its species on this planet. 'The time depth is absolutely remarkable,' notes Professor Matthew Collins, a bio-archaeologist at York and one of the authors of the study. 'Until several years ago we did not believe we would find any collagen in a skeleton of this age, even if it was as well-preserved as the West Runton Elephant,' he adds. 'We believe protein lasts in a useful form ten times as long as DNA which is normally only useful in discoveries of up to 100,000 years old in Northern Europe. The implications are that we can use collagen sequencing to look at very old extinct animals. It also means we can look through old sites and identify remains from tiny fragments of bone.' Commenting on the discovery, lead author Dr Mike Buckley of the University of Manchester says: 'What is truly fascinating is that this fundamentally important protein, which is one of the most abundant proteins in most (vertebrate) animals, is an ideal target for obtaining long lost genetic information.' The finding is an outcome of a study investigating the sequencing of mammoths and mastodons. The team compared the West Runton Elephant with other mammoths, mastodons and modern elephants. As old as it was, enough of the fossil's peptides were obtained by the researchers to identify the West Runton skeleton as elephantid. They also discriminated between elephantid and mammutid collagen. 'The West Runton Elephant is unusual in that it is a nearly complete skeleton,' explains Nigel Larkin of the Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service, a co-author of the paper. 'At the time this animal was alive, before the Ice Ages, spotted hyenas much larger than those in Africa today were scavenging most carcasses and devouring the bones as well as meat. That means most fossils found from this time period are individual bones or fragments of bone, making them difficult to identify. In the future, collagen sequencing might help us to determine the species represented by even smallest scraps of bone.' Mr Larkin says this research will play a key role for archaeological and palaeontological collections in museums and archaeology units worldwide, not just in the UK.For more information, please visit: University of York: http://www.york.ac.uk/(opens in new window) University of Manchester: http://www.manchester.ac.uk/(opens in new window) Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service: http://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/(opens in new window) Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta: http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/212/description#description(opens in new window)

Countries

United Kingdom