Archives bring to life experiences of religious minorities

Religious minorities were often repressed and persecuted during the 20th century under both fascism and communism. Creative responses to authoritarian rule have until now remained concealed in secret police archives, as have artefacts from their daily lives. The Hidden Galleries(opens in new window) project, supported by the European Research Council(opens in new window), sought to open these archives up to new audiences. Two key objectives were to recover materials that can provide a more nuanced view of life within these persecuted communities, and to better understand how these experiences continue to shape community attitudes to State institutions today. “The experiences of religious communities have tended to be addressed from a top-down perspective,” explains Hidden Galleries project coordinator James Kapaló, senior lecturer at University College Cork(opens in new window) in Ireland. “This means that academics have focused on Church-State relations, or the repression of important religious leaders. In contrast, our project looked at the everyday lives of ordinary people, to really grasp the lived experience.”

Digging into archives

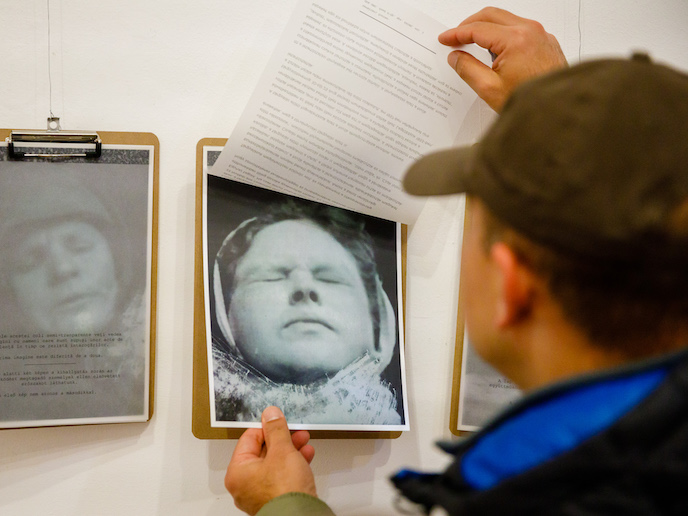

The focal point of the project’s research was the secret police archives in Hungary, Moldova, Romania and Ukraine. Within these archives, the project team sifted through copious amounts of documentation, reports and investigations in order to locate confiscated materials. “We were interested in retrieving prayer books, holy cards and icons, letters and family photos, things that might shed fresh light on everyday life,” says Kapaló. Another interesting find in the archives was visual records – photos, maps and even films – all created by the regime to negatively portray religious minorities. Kapaló was especially fascinated by these findings. “The secret police not only raided these communities and confiscated belongings; they also went to great lengths to generate visual material while conducting operations,” he adds. “These films weren’t just simple reconstructions. This forces us to reassess how anti-religious propaganda was put together.”

Shining a light

The discovery of this visual propaganda provided the project team with the inspiration of bringing this material into the open. “We didn’t want to just let this material sit in an archive,” explains Kapaló. The project was able to exhibit images on the walls of galleries, and on a dedicated website – hence the project’s title, ‘Hidden Galleries’. “This step proved very important, as it helped us to engage directly with the communities that had been targeted,” says Kapaló. Exhibiting this archived material also enabled the project team to record responses from these communities. These responses ranged from fear of what they might find in the collections to huge interest, and even a desire to create their own museums. “Dealing with secret police archives is a complex issue,” he remarks. “We need to think about ethical questions and things such as right of access, how materials are catalogued, and how to empower communities to engage with their stolen patrimony.” In addition to shining a light on the life of religious minorities under authoritarian rule, the project also sought to better understand how these experiences have helped to shape contemporary attitudes. Under communism and fascism, religious communities were often pitted against each other by the State, to shore up populist support and leverage power. This led to secrecy and distrust of State institutions and elites, phenomena that can be seen in parts of Europe today. “This project has helped us to better understand how ideas were transmitted during authoritarianism, and how resistance took shape,” adds Kapaló. “It shows us what happens when trust in so-called experts and elites is broken. The current pushback against experts and the elite can be found back in the authoritarian era.”