Linking social and cognitive networks in adolescence

Social bonds weave the fabric of interaction for many species, and have been key to human survival throughout evolution, offering security, support and comfort. While social scientists have studied the structure of modern society’s elaborate social networks, neuroscientists have investigated the brain mechanisms which enable us to navigate them. However, these research lines have largely been separated, resulting in partial explanations. Neuroimaging(opens in new window), in highly controlled laboratories, has found evidence that positive social interactions activate the same reward networks in the brain as are triggered by pleasant experiences such as food and sex.

A key developmental phase

“While this provides insights into brain functioning, social behaviour outside the MRI scanner is dynamic; individuals are not passive but interact in multiple and fluid situations. This is the domain of the social sciences,” explains Lydia Krabbendam(opens in new window), from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam(opens in new window), the project host. The SCANS project, funded by the European Research Council(opens in new window), focused on the social bonds formed in adolescence, as a key developmental phase for later social behaviour. SCANS found that an individual’s position within the social networks of the classroom correlated with levels of social trust, alongside activity in the brain’s reward network.

Entering the classroom

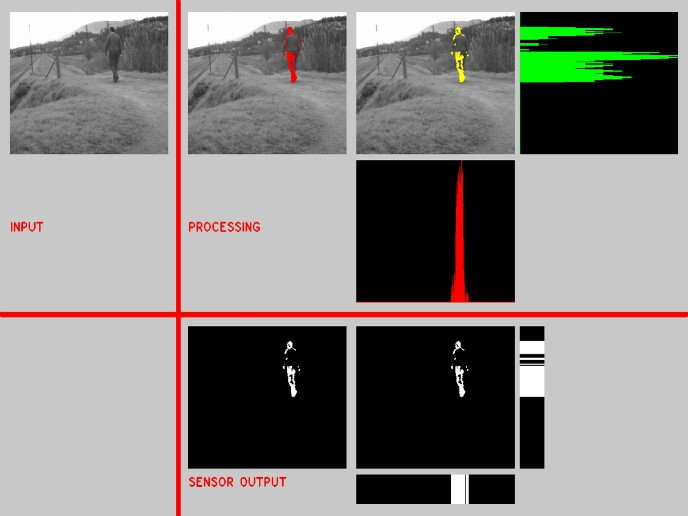

Adolescence is a key developmental phase characterised by an increased sensitivity to peer processes. These result in social reorientation, where social networks expand and become increasingly complex – processes paralleled by the maturation of social cognitive functions. “Also, psychopathologies(opens in new window) such as depression or social anxieties often manifest first during adolescence, which could be related to the increased importance of social interactions,” adds Krabbendam. As well as project coordinator Krabbendam’s background in neuropsychology, the SCANS research approach also encompassed anthropology, economics and sociology. SCANS conducted social network analyses, where relationships between individuals in a group, in this case the classroom, are examined using questionnaires. For example, SCANS asked every individual to list all their friends, or all the people they like. This resulted in a network of ties (relationships) and nodes (individuals), allowing various individual and group analyses to be conducted. These determined things like how central an individual is to a network, or how dense a group network is. These results were then analysed statistically in relation to other measures. For example social cognitive tasks were used to assess trust and the ability to take another’s perspective. Self-reported questionnaires were also used to assess potential psychopathology, such as depression.

Of bonds and brains

SCANS recruited 900 adolescents overall from more than 40 classes and managed to get participation twice a year, for 3 years, including participation of the whole class in half the cases. A particularly noteworthy finding was that the longitudinal data from both the questionnaires and the tasks, suggested ongoing development of social cognition between 12 and 15 years of age, with some interesting differences between boys and girls. “The prevailing view is that girls are better at social cognition. We found this to be true for some aspects – they showed more empathy and better perspective-taking skills – but not for others, boys showed higher trust, for example,” explains Krabbendam. Another key finding was that individuals located more centrally in the social network – having more reciprocal friendships with other central individuals – displayed higher levels of trust, with more active brain reward networks during trust decisions. “While we cannot conclude anything about cause and effect, it does highlight clear associations between social context and social brain, leaving much scope for future innovative multidisciplinary research,” concludes Krabbendam.