Why more data is not the panacea for border security

To identify and prevent the movement of people deemed potentially dangerous, data is increasingly collected and processed at national borders, increasingly using artificial intelligence (AI). This trend is raising increasing concerns about a lack of transparency around the data processing algorithms, alongside disparities in data handling between, and within, states. “EU agencies and national border authorities often see data as a universal problem solver, with little discussion about the implications and creation of new problems, impeding rather than facilitating democratic processes,” explains Claudia Aradau, coordinator of the EU-funded SECURITY FLOWS(opens in new window) project. Following the data along key European migrant routes across France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom, the team has shown that datafication is not a frictionless standardised enterprise. “We challenge the prevailing logic of datafication, that more data sharing generates richer actionable intelligence and that AI speeds up processing to ensure border security,” adds Aradau, from King’s College London(opens in new window), the project host.

Researching the impacts of datafication on stakeholders

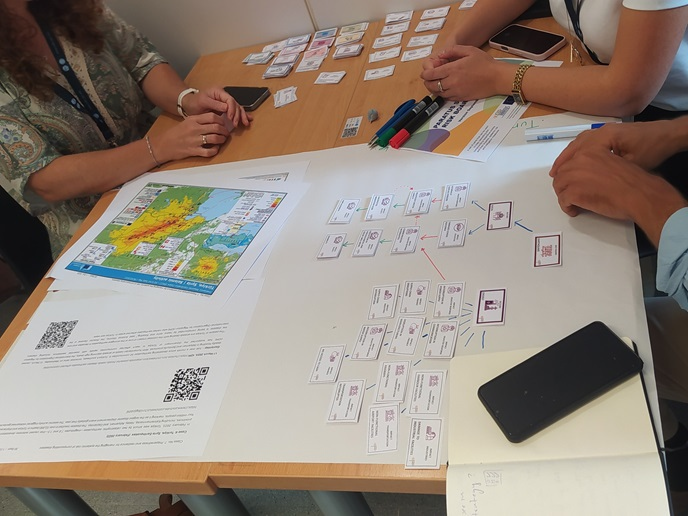

Justified by fears of information slipping through the net and the challenges of fragmented and complex databases, the European Union has launched an interoperability initiative(opens in new window) to extend data collection across existing databases, while developing three new ones. “Meanwhile, various European authorities increasingly use new forms of data gathered through controversial mobile phone screening or social media monitoring. This is not only intrusive, but can be false, out of date or unintelligible. These problems are not being sufficiently acknowledged, even as civil society actors and academics warn about them,” notes Aradau. SECURITY FLOWS, which was funded by the European Research Council(opens in new window), combined participant observation (accompanying lawyers and NGOs in their daily work, and observing events) with interviews with border authorities, lawyers, NGOs, grassroots organisations and migrants. This was complemented by documentation including legal cases, policy guidelines, training materials and research reports. “We found that data flows are characterised by fragmentation, interruption, gaps, miscommunications and failures. In many cases, data is not collected, or if collected not shared, or if shared, not always legible,” says Aradau. Data was also found to often be recorded in different formats, dependant on the digital device or software used. Data could be in paper format, needing digitisation, often hard to combine with digitally native versions. Moreover, data was found recorded in multiple EU and national databases, often dispersed and not updated. For example, while national authorities record fingerprints in automated fingerprint databases(opens in new window) (AFIS) and the Eurodac database(opens in new window) (the EU’s database for managing asylum applications), they are sometimes recorded separately. The team also found that datafication transforms the work practices of various stakeholders which now require a lot of resources.

More debate needed on social implications of datafication

Aradau argues that democracy should not be taken for granted, rather contested in physical and symbolic spaces, such as borders. “The concern is that efforts to hold authorities to account are increasingly suppressed and criminalised. Asking questions about border security also questions how the EU understands democracy,” she says. Aradau calls for three key policies when using digital technologies in justice and home affairs systems: Firstly, evaluation by expert and citizens’ assemblies, involving people with lived experiences of data and borders, to assess necessity and impact. Secondly, consideration of resource requirements. Lastly, better oversight of the engagement between European agencies and private companies. “The idea of data as a problem solver is dangerous, with many scandals about unlawful data collection and sharing practices. It is essential to understand more about the data processed, but also about the technologies used to do so,” concludes Aradau.