Leprosy transmission: the role of wild animals

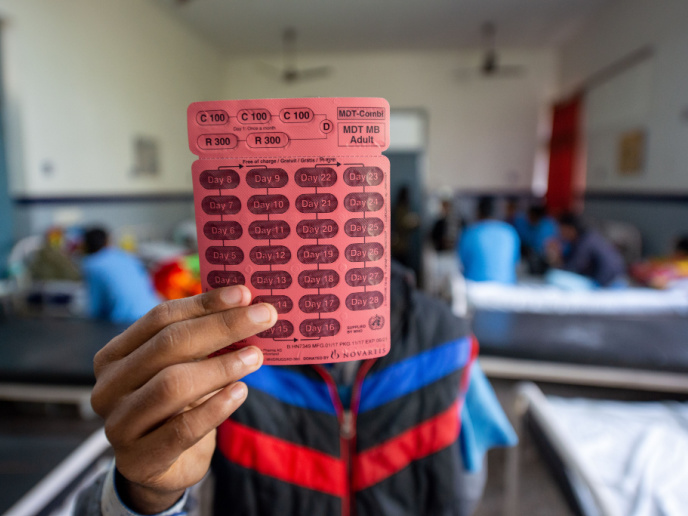

Leprosy(opens in new window) is an infectious disease caused by the slow-growing Mycobacterium leprae bacteria and affects the skin, eyes, peripheral nerves and respiratory tract. The disease was widespread in medieval Europe, and it is now restricted in tropical and subtropical regions. The breakthrough in treatment came with the anti-inflammatory and antibacterial drug dapsone(opens in new window) that required lifelong administration. Since the 1960s a combination of antibiotics is used for cure, including rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine, that has led to a significant decrease in the number of cases. Yet, there are approximately 200 000 cases every year and the emergence of drug resistance constitutes reasons for a resurgence of interest in the underlying resistance mechanisms and the mode of transmission of M. leprae.

Genetic analysis of M. leprae

The aim of the EU-funded LEPVORS project was to identify drug resistance genes and associate them with clinical phenotype. The research was undertaken with the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions(opens in new window) (MSCA) programme and involved the identification of mutations in clinical samples that can be associated with disease outcome. Researchers had to overcome the difficulty of cultivating M. leprae in the laboratory by obtaining samples directly from infected individuals. Sequencing of 150 genomes of M. leprae led to the identification of hypermutated genes in specific strains that exhibited signs of drug resistance. Results suggested a previously unknown mechanism of dapsone resistance that requires further investigation. The work also involved the analysis of clinical samples from Brazil, where some of the identified resistant strains were transmitted in patients with no family link or history of contact. “Our data suggested that the resistance to dapsone is more prevalent than what is currently reported,” explains the MSCA fellow Charlotte Avanzi.

Insight into the mechanism of transmission

For years, humans were considered the only host of M. leprae. However, recent evidence(opens in new window) indicates a bacterial reservoir in armadillos and red squirrels, suggesting zoonosis transmission. This clearly challenges the possibility for leprosy eradication. LEPVORS scientists used the genetic evidence from clinical isolates to trace the history of the strain and the disease and identify the route of transmission in the human population and in animals. They demonstrated that armadillos in Mexico(opens in new window) and wild populations of chimpanzees in Guinea-Bissau and Ivory Coast(opens in new window) are natural reservoirs for the leprosy bacilli. Interestingly, the strain circulating in armadillos was genetically very similar to the one circulating in humans in Mexico. In contrast, the wild populations of chimpanzees harboured rare and different bacterial strains. Avanzi emphasises: “It seems that the animal reservoir plays a very important role in leprosy transmission and that M. leprae may be circulating in more wild animals than initially suspected.” The existence of several reservoirs in different countries clearly indicates that programmes aiming at leprosy elimination should be revisited to also consider animal and environmental approaches to eradicate the disease.