Putting out the fire with intracellular smoke detectors

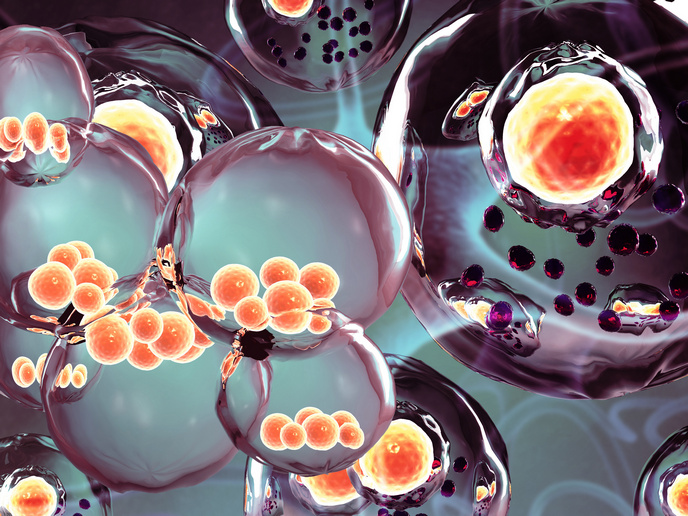

New research(opens in new window) supported in part by the EU-funded TO_AITION(opens in new window) project has revealed the existence of a novel sensor found inside the body’s cells that alerts the cell when there is damage to its energy-producing mitochondria. As reported in a news item(opens in new window) posted on ‘SciTechDaily’, when this intracellular ‘smoke detector’ does not function properly, it can lead to chronic skin conditions and could also affect heart and intestinal function. The findings were published in the journal ‘Nature Immunology’. The cells in our bodies have different sensors that issue warnings when the cell is threatened by a virus attack or some form of damage. The research team from Germany and Singapore has now identified a new sensor that monitors cell function. “We have now discovered that a molecule called NLRP10 also acts as a sensor,” explains study senior author Prof. Dr Eicke Latz of TO_AITION project partner University Hospital Bonn, Germany, in the news item. “This was completely unknown until now.” NLRP10 gained the ‘smoke detector’ moniker because it detects when the cell’s mitochondria begin to smoke as a result of a malfunction. When the sensor detects damage to mitochondria, it triggers a complicated process that creates something called an inflammasome. This multiprotein complex’s activity ultimately causes the cell to die and be disposed of by summoned immune cells.

Preventing the worst

“This process is hugely important,” remarks Prof. Dr Latz. This is because thanks to the inflammasome’s immediate action, it prevents other parts of the tissue from being damaged. “Disruption of this mechanism can result in chronic inflammation,” states the researcher. “Killing cells with mitochondrial defects may sound drastic. Ultimately, however, this step prevents more serious consequences.” NLRP10 sensors are mainly found in the outermost skin layer and help protect the skin from accumulated damage caused by UV radiation and pathogens by getting rid of affected cells. Study lead author Dr Tomasz Próchnicki, also from University Hospital Bonn, explains why it is important that these sensors function properly: “If a mutation causes the NLRP10 sensor to malfunction, this can result in a chronic skin inflammation called atopic dermatitis.” NLRP10 molecules are also found in great numbers in intestinal wall cells that regularly come into contact with pathogens and other harmful substances and in the heart where well-functioning energy supply is especially important. These particularities necessitate the quick disposal of cells with defective mitochondria. The study supported by TO_AITION (A high-dimensional approach for unwinding immune-metabolic causes of cardiovascular disease-depression multimorbidities) could lead to a better understanding of mitochondria-linked inflammatory diseases. “It is conceivable to specifically modulate the NLRP10 sensor using certain substances in order to stimulate the formation of inflammasomes,” concludes Prof. Dr Latz. “This approach might enable chronic skin diseases to be better controlled.” For more information, please see: TO_AITION project website(opens in new window)